Secrecy Systems

authored by Premmi and Beguène

Introduction

Alice, a celebrated American actor, finds herself hounded by the paparazzi on every public appearance. Craving a respite, she plans a discreet Parisian sojourn, yet longs for the companionship of her friend Bob, who resides in Rome. Alice must find a way to tell Bob to meet her in Paris, ensuring at the same time that the paparazzi remain unaware of her plans.

If Alice were to simply send the message, “Meet me in Paris on the 20th of July,” through a courier, she would have to place her complete trust in that courier. Her message’s security would be entirely dependent on the courier’s trustworthiness. Unfortunately, in reality, trust is expensive and does not scale. This presents Alice with a profound dilemma. How can Alice communicate with Bob such that even if anyone intercepts the courier and obtains the transmitted message, it reveals no information to the interceptor?

Upon pondering deeply on this issue, Alice realizes that to ensure that only Bob receives her message, irrespective of the courier’s trustworthiness, the following conditions must be fulfilled:

- Her message must be concealed from everyone except Bob, which is achieved by transforming it into a form only Bob can decipher. (Confidentiality)

- If anyone else obtains this transformed message, it should reveal nothing about the original message. (Information-Theoretic Secrecy / Semantic Security)

- When Bob receives and deciphers Alice’s message, it must be precisely the message she sent him; that is, if it were altered in transit, Bob should be able to detect that it was altered. (Integrity)

Alice realizes that she can conceal her message from everyone else except Bob if she transforms her message such that, for Bob, only Alice’s message would result in this transformed message but for everyone else, any message that Alice could have sent would be equally likely to have resulted in this transformed message.

Our goal in cryptography is to design systems that can fulfill the aforementioned criteria, namely, Confidentiality, Information-Theoretic Secrecy, and Integrity, in addition to other critical security properties such as Authentication (verifying identities) and Non-repudiation (preventing denial of actions). For the purpose of this discussion, however, we will primarily focus on laying the foundational understanding of systems that achieve confidentiality and information-theoretic secrecy by implementing Alice’s insight. It is important to reiterate that the systems considered here aim to conceal the meaning of the message, although the fact that a message is being sent (its existence) is not hidden from an interceptor. Let us proceed by mathematically defining and reasoning about such systems referred to as secrecy systems.

Secrecy Systems

A secrecy system is defined abstractly as a set of transformations of one space (the set of possible messages called the message space) into a second space (the set of possible ciphertexts called the ciphertext space). Each particular transformation of the set corresponds to enciphering with a particular key. The transformations are reversible so that unique deciphering is possible when the key is known. This concept of a secrecy system as a set of transformations is illustrated in Figure 1.

Each key (and therefore each transformation) is assumed to have an a priori probability associated with it; that is, the probability of choosing that key. Similarly, each possible message is assumed to have an associated a priori probability determined by the bias of the sender of the message (the underlying stochastic process). It is further assumed that the adversary (the unintended recipient of a message) knows these a priori probabilities for the various keys and messages as well as the secrecy system used to encipher the messages. This critical assumption, that the security of a secrecy system must not depend on the secrecy of the system itself (i.e., the set of transformations and their associated probabilities for both keys and messages) but solely on the secrecy of the key, is famously known as Kerckhoffs’ Principle.

Let us now describe how Alice uses this secrecy system to communicate secretly with Bob. Alice, at the transmitting end, produces a message and chooses a key (from a key source) in accordance with the key’s probability distribution. She sends the key to Bob through a secure channel. For now, we assume the existence of such a channel immune to eavesdropping; later, we will discuss protocols that allow Alice to securely share the key with Bob. Alice’s choice of key determines which particular transformation within the set forming the secrecy system will be used.

When Alice wishes to send a message to Bob, she applies the selected key to the message, which results in the transformation of the message into a ciphertext. This ciphertext is then transmitted to Bob via a channel which might be insecure, i.e., prone to eavesdropping by an adversary. When Bob receives the ciphertext, he applies to the ciphertext the key provided to him by Alice, which results in an inverse of the particular transformation that produced the ciphertext from the message, and hence recovers the original message.

If the ciphertext is intercepted by an adversary, he can calculate from it the a posteriori probabilities of the various possible messages and keys which might have produced this ciphertext. This set of a posteriori probabilities constitutes the adversary’s knowledge of the key and message after interception. The calculation of these a posteriori probabilities constitutes the work of a cryptanalyst (the person trying to break or decode the secrecy system).

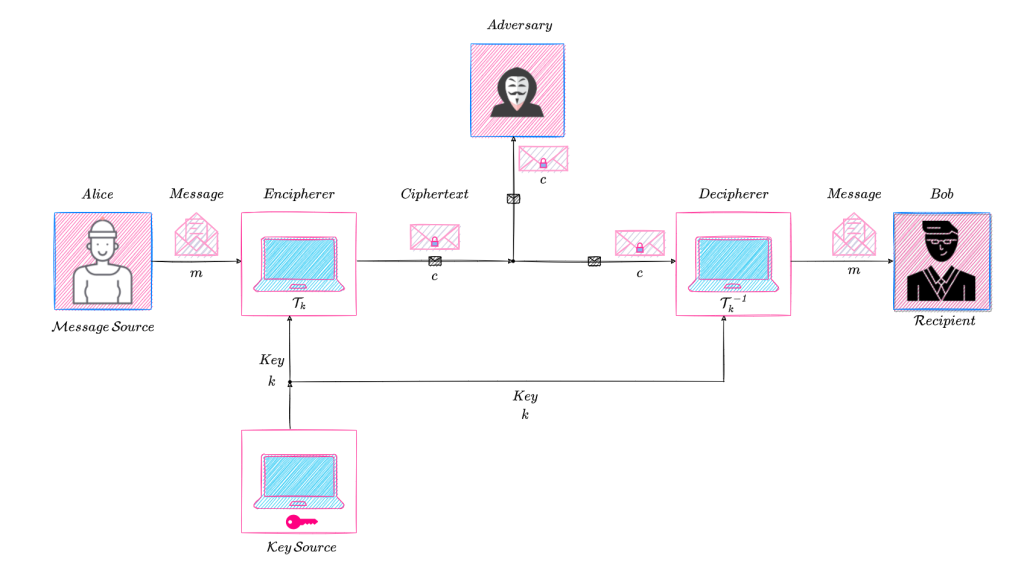

The following diagram illustrates the usage of a general secrecy system.

Focusing on the enciphering process, we can see from Figure 2 that the encipherer performs some functional operation, say \mathcal{f}, on the message \mathcal{m} and key \mathcal{k} to produce the enciphered message \mathcal{c}, also called the ciphertext.

Therefore, we have

c = f(m, k)

Since we defined a secrecy system as a set of transformations of the message space to the ciphertext space, it would be preferable to think of enciphering not as a function of two variables but as a one parameter family of transformations. Hence,

c = T_{k_i}(m)where T_{k_i} is the transformation applied to message \mathcal{m} to produce ciphertext \mathcal{c}. Here, k_i corresponds to the particular key being used, with i serving as its unique index within the key space.

The set of all possible ciphertexts that can be produced by enciphering messages from the entire message space \mathcal{M} using a specific key k_i is denoted by the image of the transformation T_{k_i}, written as T_{k_i}(\mathcal{M}).

We will assume, in general, that the key space (the set of possible keys) is finite and that each key has an associated probability p_{k_i}. Thus the key source is represented by a statistical process or device which chooses one from the set of transformations \{T_{k_0}, T_{k_1}, \cdots, T_{k_{l-1}}\} with the respective probabilities p_{k_0}, p_{k_1}, \cdots, p_{k_{l-1}}, where l is the total number of possible keys.

Similarly we will generally assume a finite number of possible messages \{m_0, m_1, \cdots, m_{n-1}\} with associated a priori probabilities q_0, q_1, \cdots, q_{n-1}, where n is the number of messages.

At the receiving end it must be possible to recover \mathcal{m}, knowing \mathcal{c} and \mathcal{k_i}. Thus each transformation T_{k_i} in the family must have a unique inverse T_{k_i}^{-1} such that T_{k_i}T_{k_i}^{-1} = I, the identity transformation. Hence,

m = T_{k_i}^{-1}(c)This inverse, T_{k_i}^{-1}, must exist uniquely for every \mathcal{c} that can be obtained from a message \mathcal{m} with a key \mathcal{{k_i}}.

With this discussion in mind, let us provide a definition of a secrecy system.

Definition

A secrecy system is a family of uniquely reversible transformations T_{k_i} of a set of possible messages into a set of ciphertexts, the transformation T_{k_i} having an associated probability p_{k_i}. Any set of entities of this type will be called a secrecy system.

The set of possible messages will be called the message space, denoted by \mathcal{M}; the set of possible ciphertexts, the ciphertext space, denoted by \mathcal{C}; and the set of keys, the key space, denoted by \mathcal{K}.

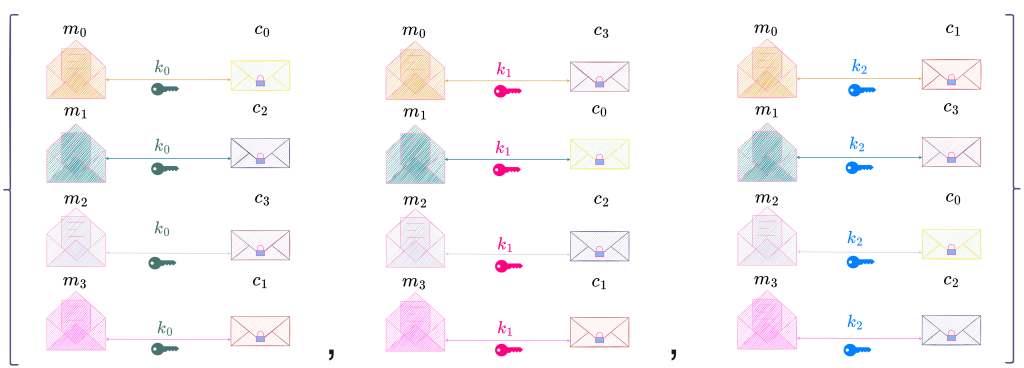

Representation of a Secrecy System

A secrecy system can be represented in various ways. We will represent a secrecy system as illustrated in Figure 3. At the left are the possible messages, each represented by an open envelope with a sheet inside and at the right are the possible ciphertexts, each represented by a closed envelope sealed with a lock. Since a particular key, say k_1 \in \mathcal{K}, transforms a message m_1 \in \mathcal{M} to a ciphertext c_0 \in \mathcal{C}, and also does an inverse transformation of c_0 to m_1, m_1 and c_0 are connected by a bi-directional line labelled k_1.

A more common way of describing a secrecy system is by specifying the enciphering and deciphering operations that transform a message to a ciphertext and vice versa using an arbitrary key. Similarly, the probabilities of various keys are also implicitly defined by describing how a key is chosen or an adversary’s habits of key choice from the perspective of a cryptanalyst. Similarly, the probabilities for messages are implicitly determined by the cryptanalyst’s a priori knowledge of an adversary’s language habits, the tactical situation influencing the content of the message and any special information available regarding the ciphertext.

Types of Secrecy Systems Based on Transformations

A secrecy system can be classified based on whether the set of all possible ciphertexts that can be produced by any given key from the set of all possible messages covers the entire ciphertext space. Such a distinction is important because it determines whether an ideally more secure secrecy system can be built by chaining together other secrecy systems as we will explain shortly.

Closed Secrecy Systems

A closed secrecy system is one in which, for each individual key k_i \in \mathcal{K}, its enciphering transformation T_{k_i}:\mathcal{M} \to \mathcal{C} is a bijection (meaning it is both one-to-one and onto). This implies that for any given key, T_{k_i} perfectly maps all messages from the message space \mathcal{M} to unique ciphertexts in the ciphertext space \mathcal{C}, and conversely, its inverse transformation T_{k_i}^{-1}:\mathcal{C} \to \mathcal{M} perfectly maps all ciphertexts from \mathcal{C} back to unique messages in \mathcal{M}.

Not Closed Secrecy Systems

Conversely, a secrecy system is not closed if for every key k_i \in \mathcal{K}, the transformation T_{k_i}:\mathcal{M} \to T_{k_i}(\mathcal{M}) is a bijection (meaning it’s one-to-one onto its own image), but there exists at least one key k_j \in \mathcal{K} such that its image T_{k_j}(\mathcal{M}) is a proper subset of the ciphertext space \mathcal{C} (i.e., T_{k_j}(\mathcal{M}) \subsetneq \mathcal{C}).

Closed vs. Not Closed Secrecy Systems

The distinction between closed and not closed secrecy systems carries important practical implications for their use. For Alice (the sender), the primary requirement is that any message can be enciphered by a key chosen by her, a capability ensured by the one-to-one property of the transformations in both closed and not closed systems. This is fundamental because the secret key is established and shared before the specific message to be transmitted is known. For Bob (the legitimate receiver), who possesses the correct key for decipherment, the nature of the system dictates the behavior when encountering ciphertexts. In a closed system, since every key’s transformation is onto the entire ciphertext space \mathcal{C}, the inverse transformation T_{k_i}^{-1} will always produce a unique, valid message from any ciphertext in \mathcal{C}. Conversely, in a not closed system, while the legitimate receiver with the correct key can always decipher ciphertexts that were actually enciphered with that key, there exist ciphertexts in \mathcal{C} that cannot be produced by certain keys’ transformations. Attempting to apply such a key’s inverse transformation T_{k_j}^{-1} to one of these ‘out-of-range’ ciphertexts (e.g., from an attacker or an error) might not yield a valid message within the message space \mathcal{M}. This characteristic of not-closed systems, where not every ciphertext in the entire space is necessarily decipherable into a valid message by the inverse transformation associated with every key, is acceptable because the receiver (Bob) only needs to decipher messages produced by his specific, shared key.

This subtle difference becomes particularly crucial when considering the construction of more complex secrecy systems by chaining together multiple transformations. While a closed system can be used to build another ideally more secure secrecy system by chaining together a series of transformations and inverse transformations, say T_{k_k}T_{k_j}^{-1}T_{k_i} where {k_i}, {k_j}, {k_k} are three different keys chosen independently (as in a variant of the Triple DES secrecy system), we cannot use a not closed system to build another secrecy system in a similar way since the operation T_{k_j}^{-1} might not result in any message in the message space.

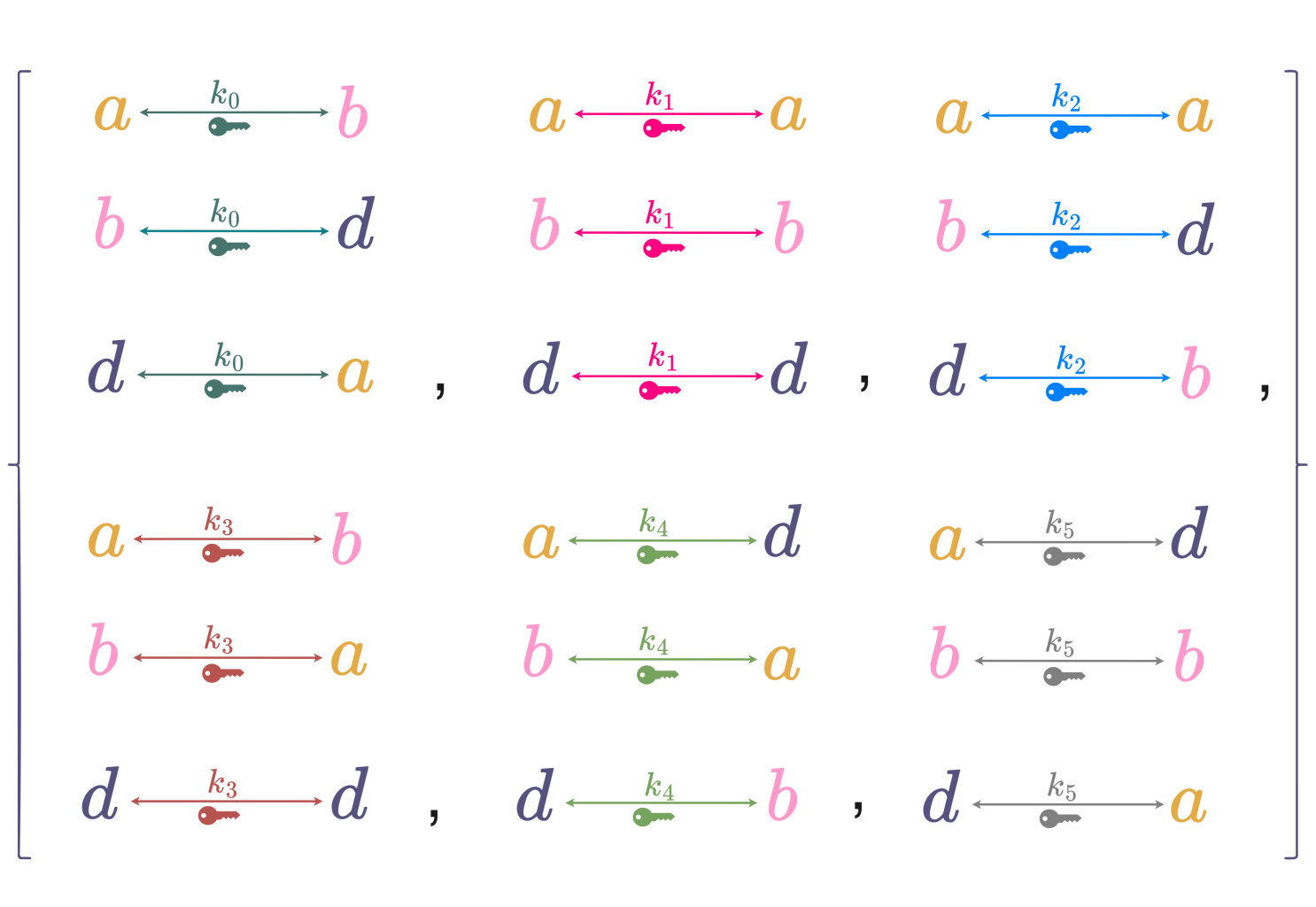

The figure 4 below illustrates an example of a closed and a not closed secrecy system.

The concepts of closed and not closed secrecy systems are important because not all arbitrary sets of transformations are suitable for building robust secrecy systems, especially those involving multiple enciphering steps.

Equivalence of Secrecy Systems

Two secrecy systems are equivalent if they consist of the same set of transformations T_{k_i}, with the same message space and ciphertext space (i.e., the same domain and range) and the same probability for all the keys.

Assumptions about the Adversary

We assume that the adversary knows the family of transformations T_{k_i}, and also the probabilities for choosing various keys. This assumption is pessimistic and hence safe, since in the long run he will eventually figure out the algorithms used to encipher and decipher the message. This assumption implies that a cryptographic system should be secure, even if everything about the system, except the key, is known to the adversary.

It should be emphasized that a secrecy system is a set of not one but many transformations as we have already illustrated in Figure 1. After a key is chosen, only one of these transformations is used. The adversary does not know which key was chosen. Indeed it is only the existence of other keys that gives the system any secrecy.

As per our definition of a secrecy system, a system with only one transformation i.e., having only one key with unit probability of being chosen, forms a degenerate kind of secrecy system. Such a system has no secrecy since the adversary finds the message by applying the inverse of this transformation, the only one in the system, to the intercepted ciphertext. The recipient of the message and the adversary possess the same information.

In general, the only difference between the recipient’s knowledge and the adversary’s knowledge is that the recipient knows the particular key that was used to encipher the message, while the adversary knows only the a priori probabilities of the various keys in the set.

The process of deciphering is that of applying the inverse of the particular transformation used in enciphering to the ciphertext. The process of breaking a cryptographic system is that of attempting to determine the message (or the particular key) given only the ciphertext and the a priori probabilities of various keys and messages.

Valuation of Secrecy Systems

How do we evaluate the usefulness of a proposed secrecy system? Among the different criteria that could be used in the evaluation of a secrecy system, these are the most important ones:

Amount of Secrecy

There are some secrecy systems that are perfect, meaning even if the adversary has unlimited time and resources (computing power), he is no better off after intercepting any amount of ciphertext than before. There are other secrecy systems, for example semantically secure systems, that despite leaking some information to the adversary would require impractical amounts of time and resources to decipher a ciphertext.

Size of Key

Since the key must be shared in a non-interceptable manner between the sender and receiver of a message, it would be desirable to have the size of the key as small as possible.

Complexity of Encipherment and Decipherment

Encipherment and decipherment should be as efficient as possible. As of this writing, this means in polynomial time since an algorithm is considered efficient if it runs in polynomial time.

Propagation of Errors

In certain types of secrecy systems, an error of one bit in enciphering or transmission could lead to a substantial number of errors in the deciphered message. It is desirable to keep these errors to a minimum.

Message Expansion

Ideally, the size of the ciphertext should be equal to the size of the message. However, some secrecy systems due to their design or how they process data, may cause the ciphertext to be larger than the plaintext due to the addition of padding, initialization vectors (IVs), message authentication codes (MACs), or other overhead. It is desirable to keep any such message expansion to a minimum to conserve bandwidth and storage.

Examples of Secrecy Systems

We will now discuss classical secrecy systems, focusing on two simple types, often referred to as ciphers, that serve as building blocks for the sophisticated secrecy systems in use today.

Substitution Cipher

In this cipher, a message is enciphered by substituting units of it with units of the same length usually composed of alphabets from the message’s language. The substitution is defined by the key. The units may be single letters (the most common), pairs of letters, triplets of letters or some combination of varying length. The receiver deciphers the message by performing the inverse substitution process to extract the original message.

There are a number of different types of substitution ciphers. A cipher that operates on single letters is called a simple substitution cipher; a cipher that operates on larger groups of letters is called polygraphic. A monoalphabetic cipher uses fixed substitution over the entire message, whereas a polyalphabetic cipher uses a number of substitutions at different positions in the message, where a unit from the message is mapped to one of several possibilities in the ciphertext and vice versa.

In a simple substitution cipher, each letter of the message is replaced by a fixed substitute, usually also a letter. Thus the message,

m = m_0m_1m_2,m_3\ldots

where m_0m_1\ldots are successive letters becomes:

c = c_0c_1c_2c_3\ldots = f(m_0)f(m_1)f(m_2)f(m_3)\ldots

where f is a function with an inverse. The key is a permutation of the alphabet of the message’s language.

Consider the following example of a simple substitution cipher. The cipher’s message space and ciphertext space are the same finite set \mathcal{X} = \{a, b, d\}. Since the number of permutations on \mathcal{X} is |\mathcal{X}|! = 3! = 6 and each key represents a unique transformation from the message space to the ciphertext space, the number of keys required to represent all the permutations is also 6.

In a digram, trigram and n-gram substitution, rather than substituting each single letter one can substitute diagrams, trigrams or n-grams. A digram substitution requires a key consisting of a permutation of 26^2 digrams (26 possibilities for the first letter and 26 for the second letter). It can be represented as a table, with the row corresponding to the first letter of the diagram and the column the second letter and entries in the table being the substitutions, usually also digrams.

In a substitution cipher, though the units themselves are altered, the units of the ciphertext are retained in the same sequence as in the message. Hence, substitution ciphers can be easily broken by analyzing the frequency distribution of the ciphertext since it follows the frequency distribution of the alphabet (or words) of the language.

Though most substitution ciphers are not in use today, modern ciphers like block ciphers (which we will discuss in detail later) use the cryptographic concept of substitution as a building block in their construction. Block ciphers use small substitution tables called S-boxes as part of their encryption process.

Transposition Cipher

In a transposition cipher, the units of the message are rearranged in a different and usually quite complex order, but the units themselves are left unchanged. In this cipher, a message is enciphered by shifting the positions held by units of the message so that the ciphertext is a permutation of the message. The permutation is defined by the key. Mathematically, a bijective function (invertible function) on the characters’ position is used to encrypt and the inverse function to decrypt.

In a transposition cipher of fixed period d, the message is divided into groups of length d and a permutation is applied to the first group, second group, etc. The permutation is the key and can be represented as a permutation of the first d integers. Thus for d = 5, we might have 5 3 2 1 4 as one possible permutation (or key). This means that

m_0\,m_1\,m_2\,m_3\,m_4\,m_5\,m_6\,m_7\,m_8\,m_9\ldots

becomes

m_5\,m_3\,m_2\,m_1\,m_4\,m_9\,m_7\,m_6\,m_5\,m_8\ldots

Since transposition does not affect the frequency of individual symbols, simple transposition can be easily detected by an adversary by doing a frequency count. If the ciphertext exhibits a frequency distribution very similar to the language of the message, the adversary would know that it is most likely a transposition. This can often be attacked by anagramming—sliding pieces of ciphertext around, then looking for sections that look like anagrams (a word formed by rearranging the letters of another, for example act formed from cat) of English words, and solving the anagrams. Once such anagrams have been found, they reveal information about the transposition pattern, which can consequently be used to find more patterns and thereby breaking the cipher.

Simpler transpositions also often suffer from the property that keys very close to the correct key will reveal long sections of legible message interspersed by gibberish.

Combination of Substitution and Transposition Ciphers

As already discussed, neither a substitution nor a transposition cipher is secure by itself.

In a substitution cipher, since the ciphertext follows the frequency distribution of the language of the message, high frequency letters (or digrams, trigrams etc) in the message result in high frequency ciphertext symbols, thereby establishing a strong statistical relationship between the message and the ciphertext. In order to make the cipher secure we need to break this relationship between message and ciphertext. If we can make the frequency distribution of the letters of the ciphertext more uniform than in the original message, then an adversary will not be able to get information about the message by looking at the ciphertext. Any non-uniformity of letters in the message needs to be redistributed across much larger structures in the ciphertext, making that non-uniformity much harder to detect. The process of dissipating the statistical structure of the message over the bulk of ciphertext is known as diffusion. The mechanism of diffusion seeks to make the statistical relationship between message and ciphertext as complex as possible such that it is impossible to recover the key by exploiting patterns in the ciphertext. Diffusion is achieved through ciphers that implement well defined and repeatable series of substitutions and permutations. In a cipher that performs a transposition after substitution, replacing high frequency ciphertext symbols with corresponding high frequency letters in the language of the message does not reveal chunks of the message because of the transposition.

Since in a transposition cipher, only the order of the letters in the message is changed, the patterns in the message are preserved; hence, reordering parts of the ciphertext and looking for anagrams and solving these anagrams would reveal the transposition pattern and hence the key. So a transposition cipher has a statistical relationship between ciphertext and key. One way to break this relationship and hence make the cipher secure is by eliminating anagrams through substitution. The mechanism of making the relationship between the statistics of the ciphertext and the value of the key as complex as possible in order to thwart key deduction is called confusion. One aim of confusion is to make it very hard to find the key even if the adversary has a large number of message-ciphertext pairs produced with the same key. Thus, even if the attacker can get some handle on the statistics of the ciphertext, the way in which the key was used to produce that ciphertext is so complex as to make it difficult to deduce the key.

To summarize, a cipher that combines both substitution and transposition, breaks the statistical relationship between message and ciphertext through diffusion made possible thorough transposition and also breaks the statistical relationship between ciphertext and key through confusion made possible through substitution.

As an example, let us consider a cipher called fractional cipher that combines both substitution and permutation to achieve secrecy.

Fractional Cipher

The fractional cipher substitutes each letter in the message with two or more letters or numbers (the substitution is determined by a lookup table, for example, a 5 \times 5 Polybius Square) and then permutes these symbols through transposition. The result may then be retranslated into the original alphabet.

Block Cipher

Many modern ciphers such as block ciphers use several rounds of substitution and permutation in their algorithms to enforce confusion and diffusion and hence achieve security.

The Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) is a block cipher that achieves robust security through excellent confusion and diffusion mechanisms. Confusion is achieved through non-linear look-up tables (a table that provides the substitution of an input byte with another byte that is the result of a non-linear transformation of the input byte) that destroy patterns that flow from the message to the ciphertext, while diffusion ensures that changing one bit of the input changes half the output bits on average. Both confusion and diffusion are repeated multiple times for each input to increase the amount of scrambling, and the secret key is mixed in at every stage to prevent attackers from pre-calculating the cipher’s output.

Conclusion

We defined systems that can effectively communicate information between two parties in the presence of an eavesdropper. We called such systems “secrecy systems”, provided a mathematical definition and also a framework to evaluate them. We ended the discussion with some examples of secrecy systems.

Next, we will explain how to design systems that provide maximum secrecy i.e., “perfectly secure” systems that leak no information about the message that it encrypts and why such systems are impractical to use.

Follow-up: Perfect Secrecy