authored by Premmi and Beguène

Prerequisite : Probability Primer

Follow up to : What is Security?

Now that we have defined a secrecy system and discussed how to evaluate it, let us construct one based on the first and most important criterion, namely, a secrecy system that optimizes for secrecy i.e., a system that provides maximum secrecy. Such a secrecy system is called a perfectly secure system.

Perfect Secrecy

How can a secrecy system provide maximum secrecy?

A secrecy system which is perfectly secure i.e., one which is maximally secure would provide no information about any of the messages it enciphers even if an adversary has unlimited time and computing resources to analyze any number of ciphertexts enciphered by the system.

Now that we have agreed on the defining characteristic of a perfectly secure secrecy system, let us translate this characteristic into mathematics and analyze the properties of such a secrecy system.

Let us assume that the possible messages m_0, m_1, \ldots, m_{n-1} (where n is the number of possible messages) are finite in number and their corresponding a priori probabilities are P(m_0), P(m_1), \ldots, P(m_{n-1}) and that these messages are enciphered into possible ciphertexts c_0, c_1, \ldots, c_{m-1} (where m is the number of possible ciphertexts) by

c = T_i\,m

where T_i is the transformation applied to message m to produce ciphertext c. The index i corresponds to the particular key being used.

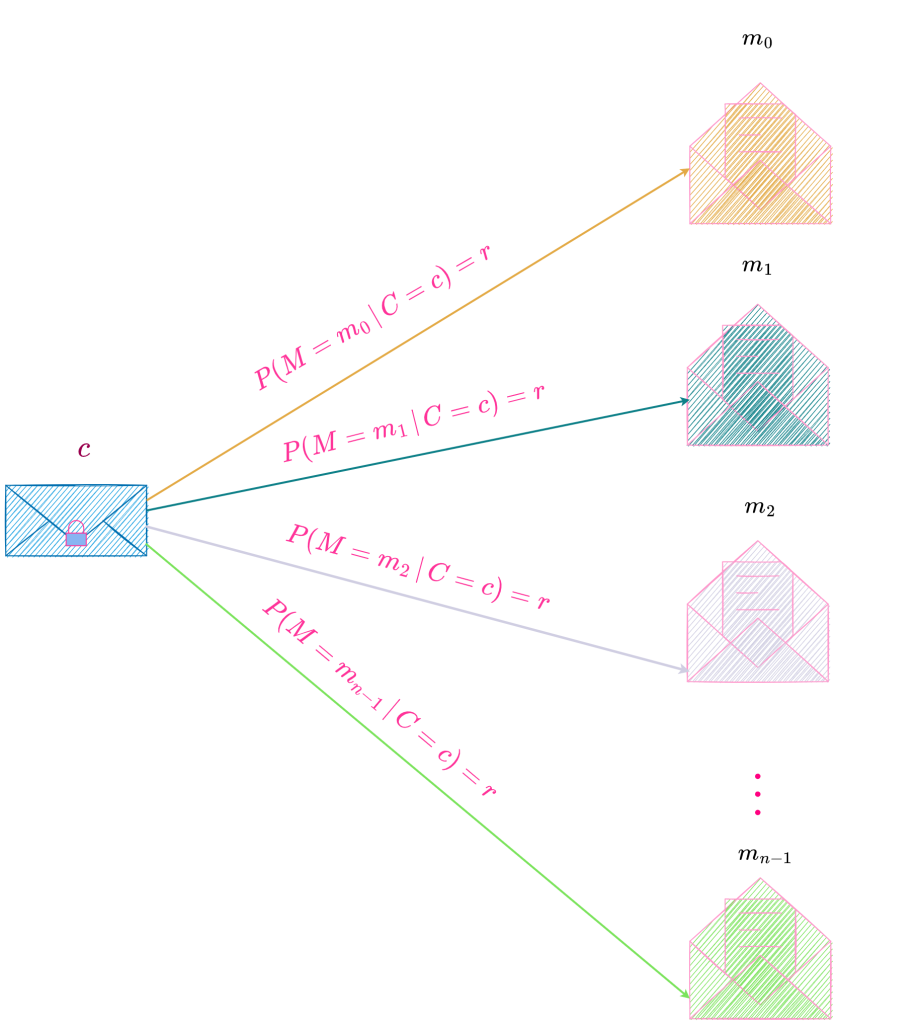

The adversary intercepts a particular ciphertext c and can then calculate, in principle at least, the a posteriori probabilities, P(M = m\,|\, C = c) for the various messages, where P(M = m\,|\, C = c) denotes the a posteriori probability of message m if ciphertext c is intercepted. Here M denotes the random variable defined on the message space (set of possible messages) and C, the random variable defined on the ciphertext space (set of possible ciphertexts).

How can a ciphertext reveal (or leak) no information about the message it represents?

Suppose an adversary with unlimited time and computing resources intercepts a ciphertext and constructs the distribution of the a posteriori probabilities of the various messages the ciphertext could decrypt to. In order for the adversary to gain no information from this distribution, it should be one of minimum information or equivalently, maximum entropy. Since the uniform distribution is the maximum entropy distribution among all discrete distributions, the distribution of a posteriori probabilities, namely, P(M = m\,|\, C = c) for various messages, should be uniform. Therefore, under this distribution, an intercepted ciphertext is equally likely to represent any of the possible messages. Hence, the adversary is forced to use his a priori knowledge of the message distribution, namely, P(M = m), to decipher the ciphertext since the intercepted ciphertext is equally likely to be the representation of any message in the message space and consequently, provides no information about which particular message it represents.

Mathematically, we can represent this by the equation, P(M = m\,|\, C = c) = P(M = m).

It should be noted that since a message is not picked at random but depends on the information a person wants to communicate, it has low entropy. Hence, a ciphertext can be viewed as the result of a transformation of a low entropy (high information) message into one of high entropy (low information). Hence, P(M = m\,|\, C = c) is uniform for various messages, though, the distribution of messages, P(M = m) is very rarely uniform.

Definition

Perfect secrecy is defined by the condition that for every ciphertext c, the a posteriori probabilities of the various messages representing this ciphertext are equal to the a priori probabilities of the same messages.That is,

P(M = m\,|\, C = c) = P(M = m)

for all m and c.

This equation implies that the random variables M \text{ and } C are independent i.e., the message and ciphertext distributions are independent which is a consequence of the message leaking no information to the ciphertext and hence the adversary gaining no information from the intercepted ciphertext.

Before we proceed further the above equation requires some clarification. This equation does not mean that the a posteriori probabilities of the various messages representing the ciphertext c, namely, P(M = m\,|\, C = c), are equal to the a priori probabilities of the messages, namely, P(M = m). On the contrary, it means that since the a posteriori probabilities, P(M = m\,|\, C = c), give no information about the particular message that was encrypted by the ciphertext, the adversary is forced to use his knowledge of the a priori probabilities of the various messages, namely, P(M = m), to guess the message that the intercepted ciphertext represents.

Necessary and Sufficient Condition for Perfect Secrecy

How do we prove that a secrecy system is perfectly secure? Based on our discussion, let us now formulate a necessary and sufficient condition for perfect secrecy. A secrecy system is perfectly secure only if it satisfies this condition, otherwise it is not perfectly secure.

A necessary and sufficient condition for perfect secrecy can be found as follows.

According to Bayes’ theorem, for discrete random variables X \text{ and } Y, we have

P(Y = y\,|\,X = x) = \frac{P(Y = y)\, P(X = x \,|\,Y = y)}{P(X = x)}.Hence, by Bayes’ theorem,

\begin{equation*}

\begin{split}

P(M = m\,|\,C = c) &= \frac{P(M = m)\, P(C = c \,|\,M = m)}{P(C = c)} \\

\text{where,} \quad \quad \quad \quad \quad \,\,\\

P(M = m) &= \textit{a priori } \text{probability of message } m, \\

P(C = c\,|\,M = m) &= \text{conditional probability of ciphertext \textit{c} if message \textit{m} is chosen} \\

&\quad \,\,\, \text{i.e., the sum of the probabilities of all keys that produce ciphertext \textit{c} from message \textit{m},} \\

P(C = c) &= \text{the probability of obtaining ciphertext \textit{c} from any cause,} \\

P(M = m\,|\,C = c) &= \textit{a posteriori \text{probability of message \textit{m} if ciphertext \textit{c} is intercepted}}.

\end{split}

\end{equation*} We have already discussed that for perfect secrecy to hold,

P(M = m\,|\,C = c) = P(M = m)

for all c \text{ and all } m.

Hence, either P(M = m) = 0, in which case P(M = m\,|\,C = c) = 0 or

\frac{P(C = c \,|\,M = m)}{P(C = c)} = 1which implies,

P(C = c \,|\,M = m) = P(C = c)

for every m \text{ and } c.

We exclude the solution P(M = m) = 0 because we want the condition for perfect secrecy, P(M = m\,|\,C = c) = P(M = m), to hold good independent of the value of P(M = m).

For perfect secrecy to hold, it must be the case that

P(M = m \,|\,C = c) = P(M = m)

for all c \text{ and all } m.

If

P(C = c \,|\,M = m) = P(C = c) \neq 0

for every m \text{ and } c, then

P(M = m \,|\,C = c) = P(M = m)

for all c \text{ and all } m and hence we have perfect secrecy.

It should be noted that the equation P(C = c \,|\,M = m) = P(C = c) is of more interest to the designer of a perfect secrecy system than a cryptanalyst, while P(M = m \,|\,C = c) = P(M = m) is of more interest to a cryptanalyst.

Therefore, we have the following result:

A necessary and sufficient condition for perfect secrecy is that

P(C = c \,|\,M = m) = P(C = c)

for all m \text{ and } c; i.e., random variables M \text{ and } C are independent. This implies that the message and the ciphertext distributions are independent of each other.

Design Constraints on a Perfect Secrecy System

In order to construct a perfect secrecy system, we need to understand the constraints imposed by this equation on the design of such a system.

So what are the consequences of this equation?

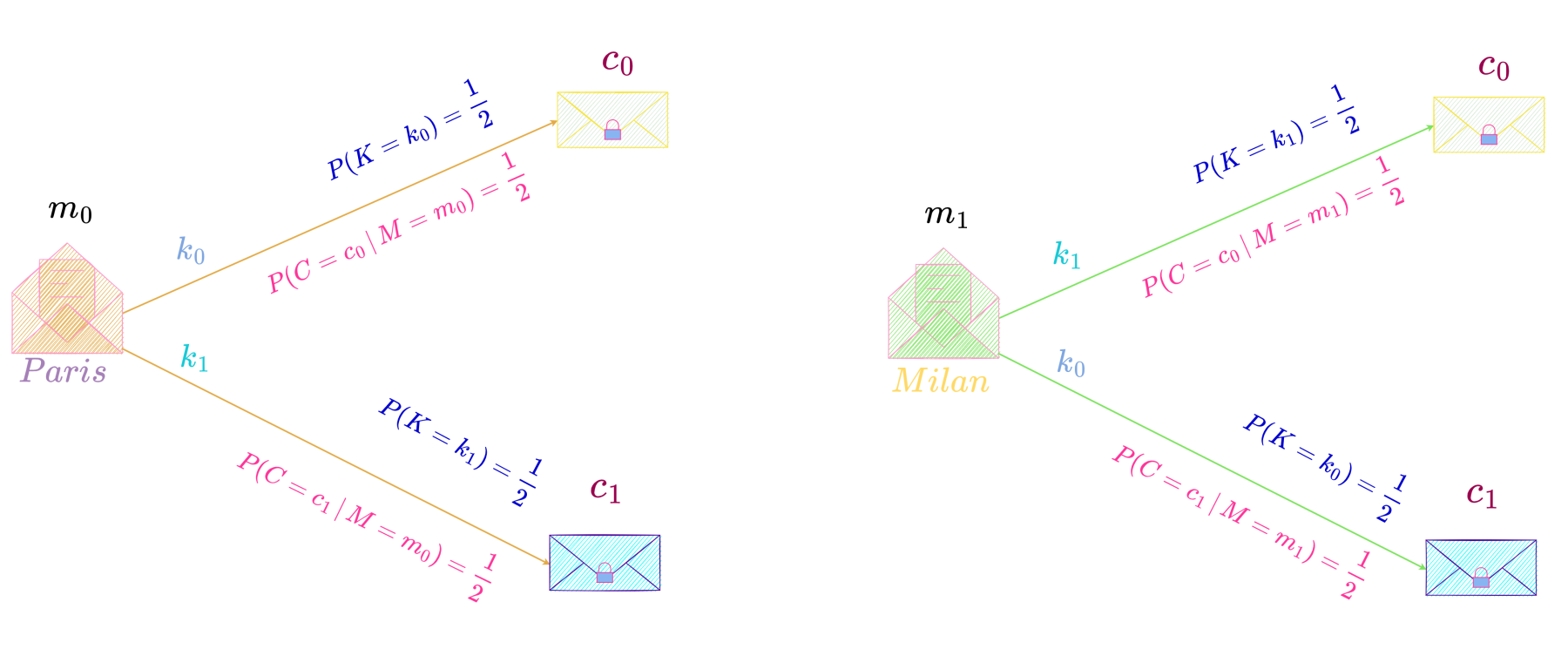

Since M \text{ and } C are independent, it implies that the choice of a particular message m does not affect the probability of obtaining a particular ciphertext c. Therefore, every message m in the message space M should represent (or encipher to) a particular ciphertext c in the ciphertext space C with equal probability. This conclusion agrees with the above equation. Since,

\begin{align*}

P(C = c \,|\,M = m_0) &= P(C = c) \,\&\\

P(C = c \,|\,M = m_1) &= P(C = c) \,\&\\

&\vdots \\

P(C = c \,|\,M = m_{n-1}) &= P(C = c) \\

\end{align*}it follows that,

P(C = c \,|\,M = m_0) = P(C = c \,|\,M = m_1) = \cdots = P(C = c \,|\,M = m_{n-1})for all c \in C and all m_i \in M, where i denotes the index of the message and takes values from 0 \text{ to } n-1. Here n is the number of messages in the message space M.

Since the transformation of a message into a ciphertext corresponds to enciphering with a key, the above equation implies that the total probability of all keys that transform a message m_i into a given ciphertext c is equal to that of all keys transforming message m_j into the same ciphertext c, for all c, m_i \text{ and } m_j. Here i \text{ and }j denote the index of a message and take values from 0 \text{ to } n-1.

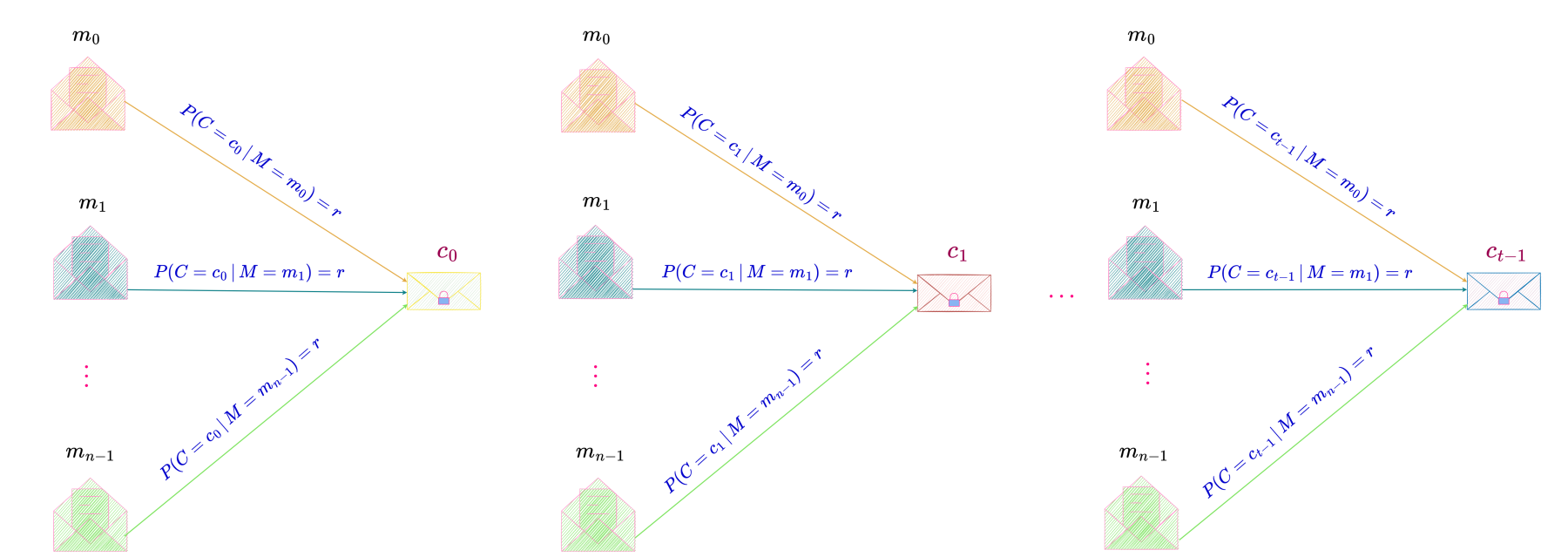

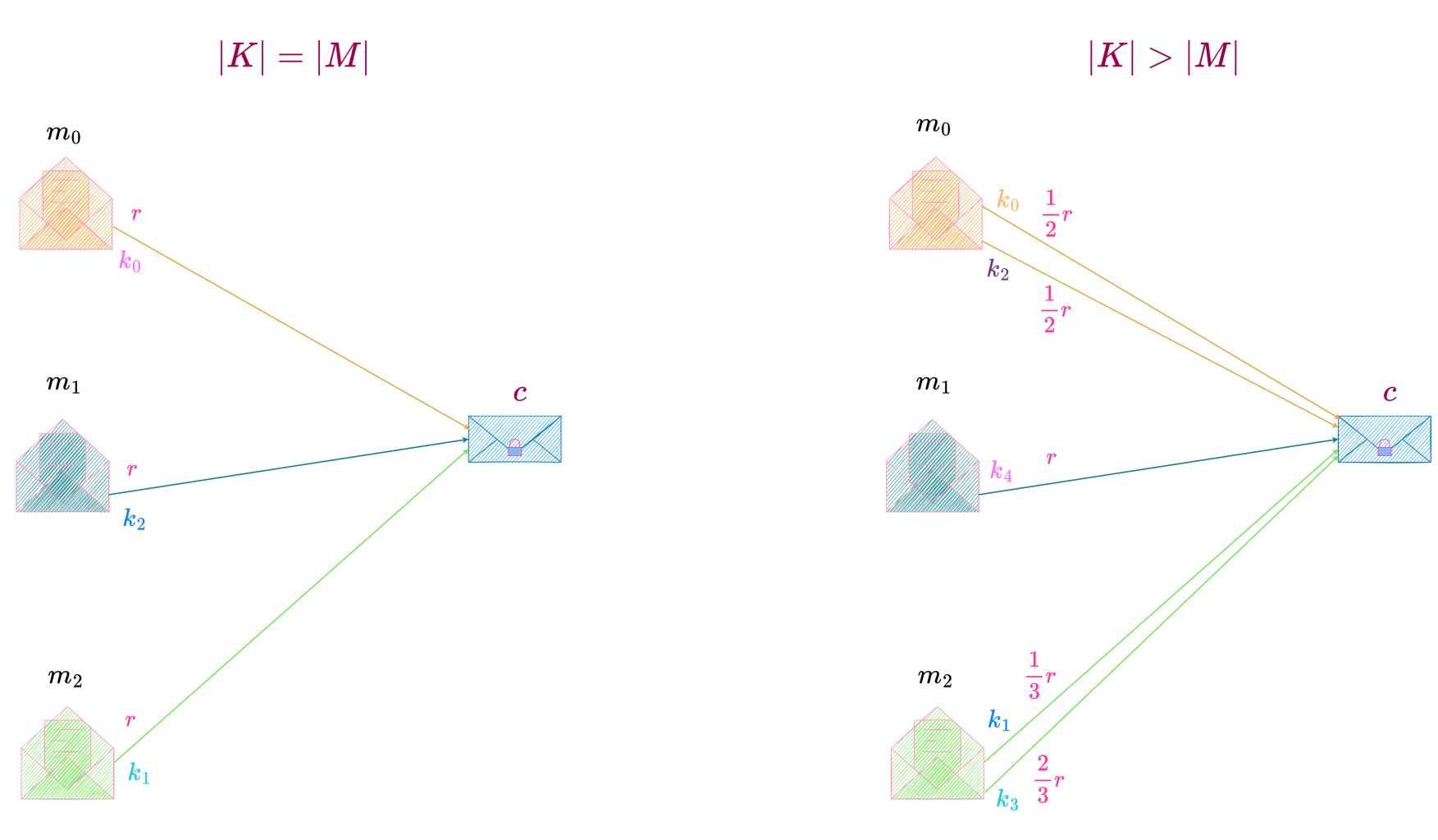

This is illustrated below. Here r is the total probability of all the keys that transform any message m_i to a ciphertext c.

It should be noted that only the total probability of all the keys transforming a message to a ciphertext needs to be equal to that of all the keys transforming any other message to the same ciphertext. The number of keys transforming a message to a ciphertext need not be equal to the number of keys transforming another message to the same ciphertext. Also the keys need not be equally likely i.e., each key can have its own associated probability different from other keys.

A key which enciphers a particular message m into a ciphertext c also deciphers c into the same message m. Hence, the total probability of all keys that transform a message m_i into a given ciphertext c is equal to that of all keys transforming the ciphertext c into the same message m_i, for all c \text{ and } m_i. That is, for every c \in C,

\begin{align*}

P(C = c \,|\,M = m_0) &= P(M = m_0 \,|\,C = c) \,\&\\

P(C = c \,|\,M = m_1) &= P(M = m_1 \,|\,C = c) \,\&\\

&\,\,\,\vdots \\

P(C = c \,|\,M = m_{n-1}) &= P(M = m_{n-1} \,|\,C = c) \\

\end{align*}We have already shown that,

P(C = c \,|\,M = m_0) = P(C = c \,|\,M = m_1) = \cdots = P(C = c \,|\,M = m_{n-1})for all c \in C.

Hence,

P(M = m_0 \,|\,C = c) = P(M = m_1 \,|\,C = c) = \cdots = P(M = m_{n-1} \,|\,C = c)for all c \in C.

This is illustrated below.

Distribution of Ciphertexts

We will next discuss whether the equation for perfect secrecy constrains the distribution of the ciphertexts in anyway i.e., does it necessitate the ciphertexts to have a particular distribution?

For perfect secrecy,

P(C = c \,|\, M = m) = P(C = c) \neq 0

for every c \in C \text{ and } m \in M.

The following is the necessary and sufficient condition for perfect secrecy enumerated for every m \text{ and } c.

\begin{align*}

\small P(C = c_0 \,|\,M = m_0) &= \small P(C = c_0) = r_0 \,\,\& \quad \small P(C = c_1 \,|\,M = m_0) = \small P(C = c_1) = r_1\,\,\& \quad \cdots \quad \small P(C = c_{t-1} \,|\,M = m_0) = \small P(C = c_{t-1}) = r_{t-1}\,\,\&\\

\\

\small P(C = c_0 \,|\,M = m_1) &= \small P(C = c_0) = r_0 \,\,\& \quad \small P(C = c_1 \,|\,M = m_1) = \small P(C = c_1) = r_1\,\,\& \quad \cdots \quad \small P(C = c_{t-1} \,|\,M = m_1) = \small P(C = c_{t-1}) = r_{t-1}\,\,\&\\

\\

&\,\,\,\vdots \quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\,\,\,\,\,\,\vdots \quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\vdots\\

\\

\small P(C = c_0 \,|\,M = m_{n-1}) &= \small P(C = c_0) = r_0 \quad \quad \small P(C = c_1 \,|\,M = m_{n-1}) = \small P(C = c_1) = r_1\quad \cdots \quad\small P(C = c_{t-1} \,|\,M = m_{n-1}) = \small P(C = c_{t-1}) = r_{t-1} \\

\end{align*}Here m is the number of messages in the message space and t is the number of ciphertexts in the ciphertext space.

These sets of equations are illustrated below :

We have already seen that a perfect secrecy system satisfies the following equation

P(M = m \,|\, C= c) = P(M = m)

for all c \text{ and } m.

Hence,

\begin{align*}

P(M = m_0 \,|\, C= c_0) &= P(M = m_0) \,\& \\

P(M = m_0 \,|\, C= c_1) &= P(M = m_0) \,\& \\

&\,\,\,\vdots \\

P(M = m_0 \,|\, C= c_{t-1}) &= P(M = m_0) \,\& \\

\end{align*}Therefore,

P(M = m_0 \,|\, C= c_0) = P(M = m_0 \,|\, C= c_1) = \cdots = P(M = m_0 \,|\, C= c_{t-1})We have already shown above that

\begin{align*}

P(C = c_0 \,|\,M = m_0) &= P(M = m_0 \,|\,C = c_0) \,\&\\

P(C = c_1 \,|\,M = m_0) &= P(M = m_0 \,|\,C = c_1) \,\&\\

&\,\,\,\vdots \\

P(C = c_{t-1} \,|\,M = m_0) &= P(M = m_0 \,|\,C = c_{t-1}) \\

\end{align*}Therefore,

P(C = c_0 \,|\, M= m_0) = P(C = c_1 \,|\, M = m_0) = \cdots = P(C = c_{t-1} \,|\, M= m_0)The necessary and sufficient condition for perfect secrecy states that,

\begin{align*}

P(C = c_0 \,|\,M = m_0) &= P(C = c_0) \,\&\\

P(C = c_1 \,|\,M = m_0) &= P(C = c_1) \,\&\\

&\,\,\,\vdots \\

P(C = c_{t-1} \,|\,M = m_0) &= P(C = c_{t-1}) \\

\end{align*}Therefore,

P(C = c_0) = P(C = c_1) = \cdots = P(C = c_{t-1})Hence in a perfectly secure system the ciphertext distribution is uniform.

These relationships are illustrated below:

Relationship between |K| and |C|

For perfect secrecy,

P(C = c \,|\, M = m) = P(C = c) \neq 0

for every c \in C \text{ and } m \in M.

We have already shown above that any message in the message space enciphers to any ciphertext in the ciphertext space with equal and non-zero probability i.e., the value of P(C = c \,|\, M = m) is non-zero and the same for any c \in C \text{ and } m \in M.

The following is the enumeration of this result for every m \in M \text{ and } c \in C.

\begin{align*}

\small P(C = c_0 \,|\,M = m_0) &= \small P(C = c_0) = r \,\,\& \quad \small P(C = c_1 \,|\,M = m_0) = \small P(C = c_1) = r\,\,\& \quad \cdots \quad \small P(C = c_{t-1} \,|\,M = m_0) = \small P(C = c_{t-1}) = r\,\,\&\\

\\

\small P(C = c_0 \,|\,M = m_1) &= \small P(C = c_0) = r \,\,\& \quad \small P(C = c_1 \,|\,M = m_1) = \small P(C = c_1) = r\,\,\& \quad \cdots \quad \small P(C = c_{t-1} \,|\,M = m_1) = \small P(C = c_{t-1}) = r\,\,\&\\

\\

&\,\,\,\vdots \quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\,\,\,\,\,\,\vdots \quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\quad\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\vdots\\

\\

\small P(C = c_0 \,|\,M = m_{n-1}) &= \small P(C = c_0) = r \quad \quad \small P(C = c_1 \,|\,M = m_{n-1}) = \small P(C = c_1) = r\quad \cdots \quad\small P(C = c_{t-1} \,|\,M = m_{n-1}) = \small P(C = c_{t-1}) = r \\

\end{align*}There are n messages in the message space and t ciphertexts in the ciphertext space.

Below is an illustration of this result i.e., every message in the message space enciphering to every ciphertext in the ciphertext space with equal and non-zero probability, r.

Since P(C = c \,|\, M = m) = P(C = c) \neq 0 for any c \in C \text{ and any } m \in M, it must be the case that there is at least one key transforming any m into any of the possible c\text{'s}.

But all the keys transforming a particular message m into different c\text{'s} must be different so that given a message and a key unique encipherment is possible i.e., a key transforms a message into exactly one ciphertext. Therefore, the number of keys is at least equal to the number of ciphertexts, i.e., |K| \geq |C|.

Since a key is first chosen and shared independent of the message that needs to be communicated, it means that a key should be able to encrypt any message in the message space. Hence every key in the key space can encipher any message in the message space.

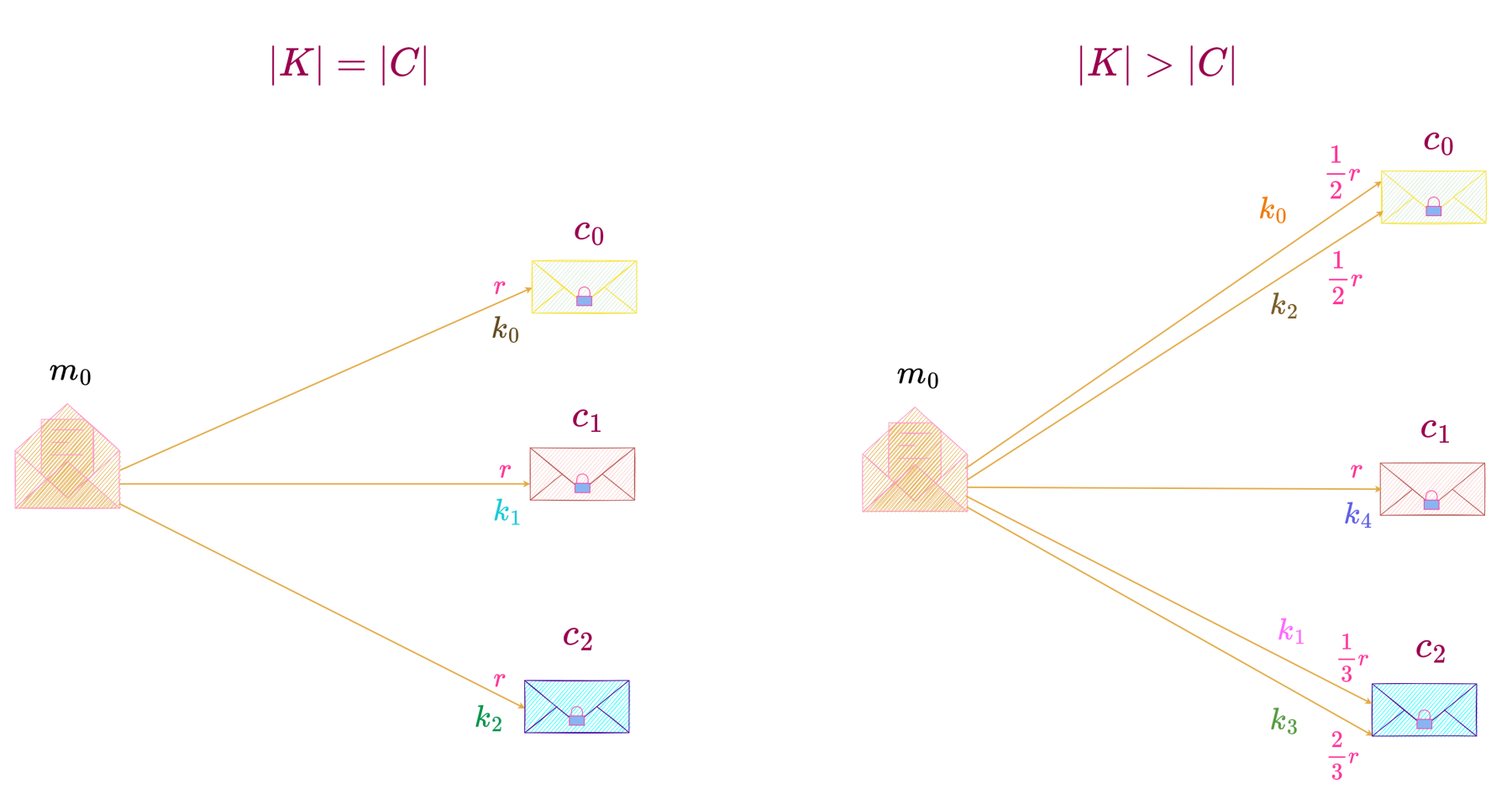

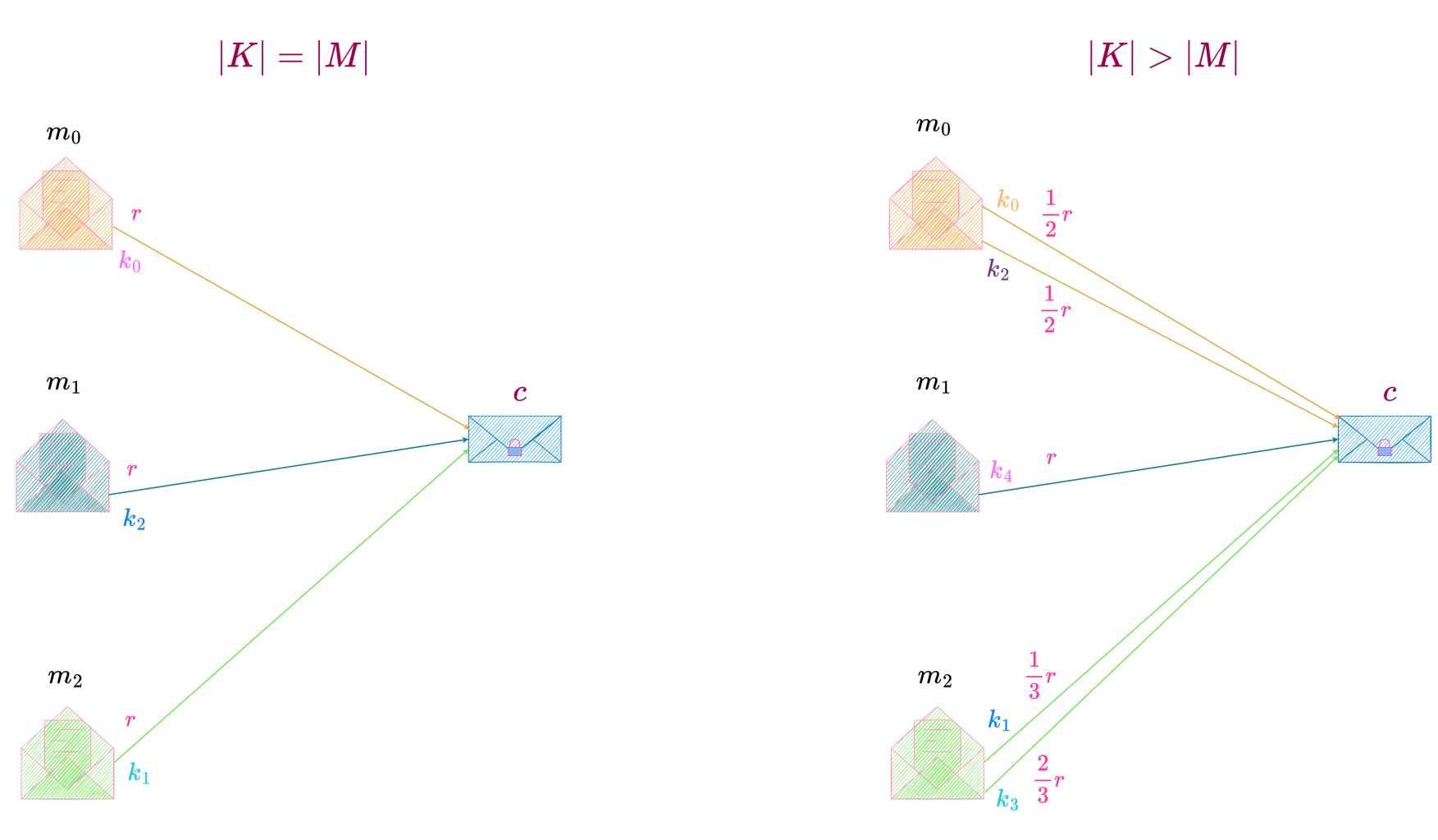

These two cases, |K| = |C| \text{ and } |K| > |C| are illustrated below.

We have already proved that,

P(C = c_0 \,|\, M= m_0) = P(C = c_1 \,|\, M = m_0) = P(C = c_2 \,|\, M= m_0)

Hence, as shown in the illustration above, a particular message in the message space can be transformed into a ciphertext by one or more keys depending on the probability distribution of the keys such that the total probability of all keys that transform the message into a ciphertext is equal to that of all keys that transform the same message to any other ciphertext in the ciphertext space.

We will next consider in some detail examples of perfect secrecy systems with |K| = |C| \text{ and } |K| > |C|.

For the case |K| = |C|, we consider a perfect secrecy system with

M = \{m_0, m_1, m_2\}, K = \{k_0, k_1, k_2\} \text{ and } C = \{c_0, c_1, c_2\}, as shown below.

Since the transformation of a message into a ciphertext corresponds to enciphering with a particular key, the probability of a message resulting in a particular ciphertext equals the sum of probabilities of all keys that transform the message into that ciphertext (since given those keys, a message results in a particular ciphertext with probability 1, i.e., P(C = c \,|\, M = m, K = k) = 1 \,\forall\, \{k : c = T_k\, m\} where T_k is the transformation applied to message \mathcal{m} to produce ciphertext \mathcal{c}. The index k corresponds to the particular key being used.)

Expressed as an equation,

P(C = c \,|\, M = m) = \sum_{k \,\in\, K} P(K = k)\, P(C = c \,|\, M = m, K = k)

In the above example,

\begin{equation*}

\begin{split}

P(C = c_0 \,|\, M = m_0) & = \sum_{k \,\in\, K} P(K = k)\, P(C = c_0 \,|\, M = m_0, K = k) \\

& = P(K = k_0)\, P(C = c_0 \,|\, M = m_0, K = k_0) \\

& \quad+ P(K = k_1)\, P(C = c_0 \,|\, M = m_0, K = k_1)\\

& \quad + P(K = k_2)\, P(C = c_0 \,|\, M = m_0, K = k_2) \\

& = P(K = k_0) \times 1 + P(K = k_1) \times 0 + P(K = k_2) \times 0 \\

& = P(K = k_0)

\end{split}

\end{equation*} Since P(C = c_0 \,|\, M = m_0) = r, P(K = k_0) =r. Similarly, P(K = k_1) =r \text{ and } P(K = k_2)=r.

Therefore,

P(K = k_0) = P(K = k_1)=P(K = k_2)

i.e., when |K| = |C|, the distribution of keys is uniform.

Since P(C = c_0 \,|\, M= m_0) = P(C = c_1 \,|\, M = m_0) = P(C = c_2 \,|\, M= m_0) = r, i.e., the total probability of all keys transforming the message to a particular ciphertext equals that of all keys transforming the same message to any other ciphertext and there is only one key transforming the message to a particular ciphertext, each key has an equal probability, r, of being picked.

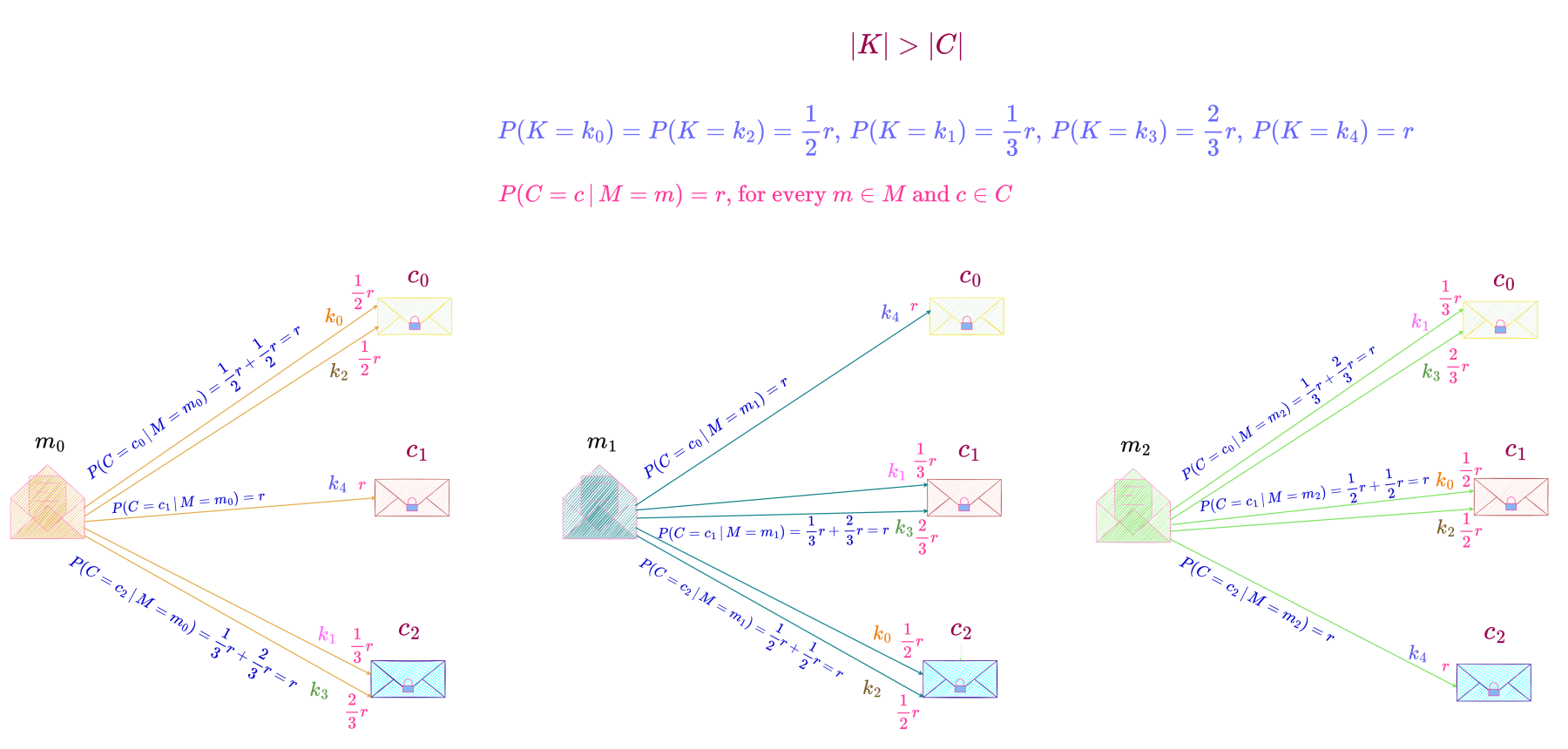

For the case |K| > |C|,

we consider a perfect secrecy system with M = \{m_0, m_1, m_2\}, K = \{k_0, k_1, k_2, k_3, k_4\} \text{ and } C = \{c_0, c_1, c_2\}, as shown below.

For this perfect secrecy system,

\begin{equation*}

\begin{split}

P(C = c_0 \,|\, M = m_0) & = \sum_{k \,\in\, K} P(K = k)\, P(C = c_0 \,|\, M = m_0, K = k) \\

& = P(K = k_0)\, P(C = c_0 \,|\, M = m_0, K = k_0) \\

& \quad+ P(K = k_1)\, P(C = c_0 \,|\, M = m_0, K = k_1)\\

& \quad + P(K = k_2)\, P(C = c_0 \,|\, M = m_0, K = k_2) \\

& \quad + P(K = k_3)\, P(C = c_0 \,|\, M = m_0, K = k_3) \\

& \quad + P(K = k_4)\, P(C = c_0 \,|\, M = m_0, K = k_4) \\

& = P(K = k_0) \times 1 + P(K = k_1) \times 0 + P(K = k_2) \times 1 + P(K = k_3) \times 0 + P(K = k_4) \times 0\\

& = P(K = k_0) + P(K = k_2) \\

\end{split}

\end{equation*} Since P(C = c_0 \,|\, M = m_0) = r,

P(K = k_0) + P(K = k_2) = r

Similarly,

\begin{equation*}

\begin{split}

P(K = k_1) + P(K = k_3) &= r \,\&\\

P(K = k_4) &= r \\

\end{split}

\end{equation*} In this perfect secrecy system, each message can be transformed into a particular ciphertext by either one or two keys. Since a message can be enciphered by every key in the key space, each key has a non-zero probability of being chosen and as can be seen from the above equations, the distribution of keys is non-uniform.

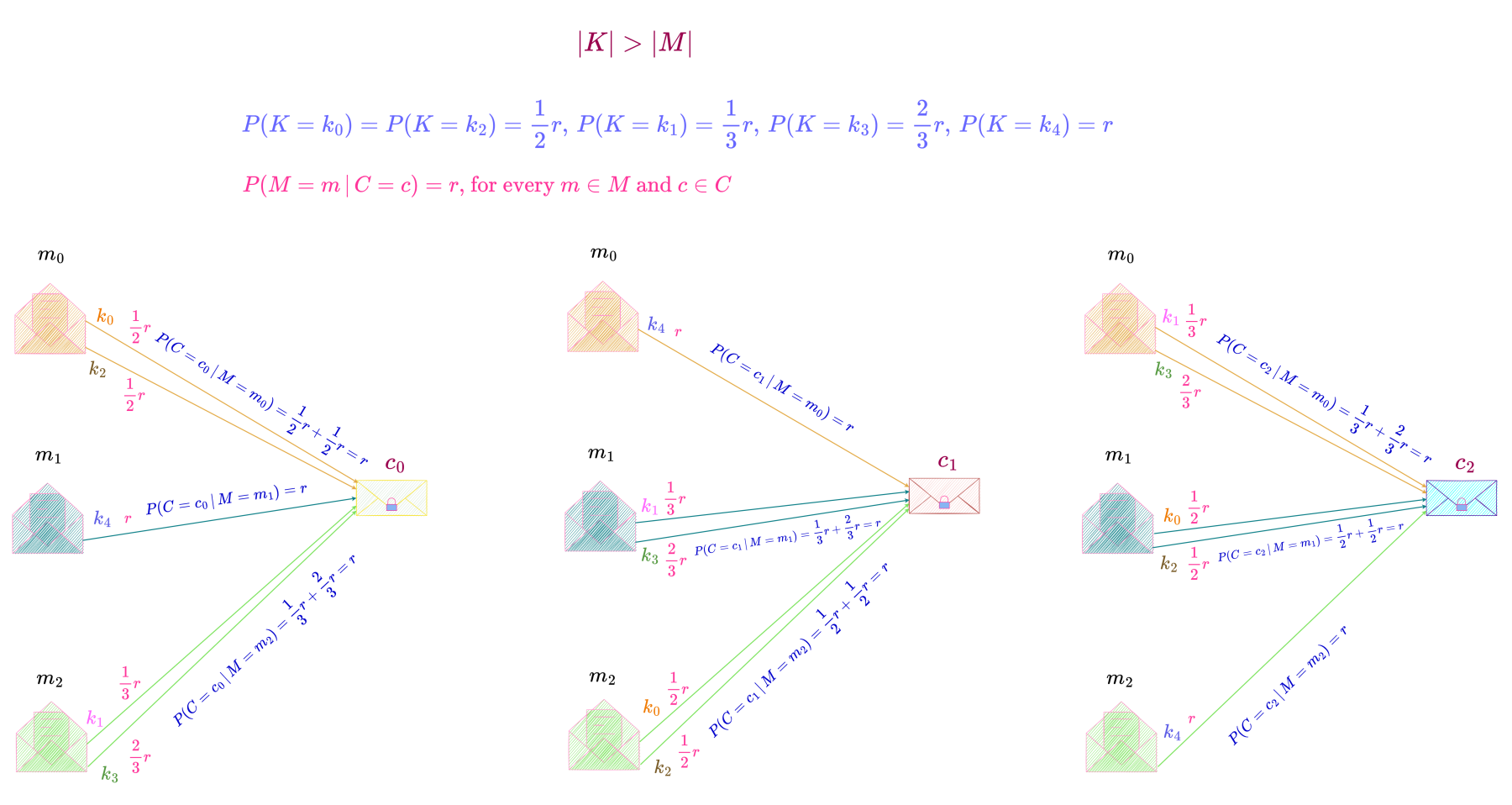

This perfect secrecy system with one possible probability distribution of keys is shown below.

Here,

\begin{align*}

P(K = k_0) &= P(K = k_2) = \frac{1}{2}r \\

P(K = k_1) &= \frac{1}{3}r \\

P(K = k_3) &= \frac{2}{3}r \\

P(K = k_4) &= r \\

\end{align*}Since by the axiom of probability,

P(K = k_0) + P(K = k_1) + P(K = k_2) + P(K = k_3) + P(K = k_4) = 1

it follows that,

\begin{align*}

\frac{1}{2}r + \frac{1}{3}r + \frac{1}{2}r + \frac{2}{3}r + r &= 1 \\

3r &= 1 \\

r &= \frac{1}{3} \\

\end{align*}Hence,

\begin{align*}

P(K = k_0) &= P(K = k_2) = \frac{1}{2}r = \frac{1}{2} \times \frac{1}{3} = \frac{1}{6} \\

P(K = k_1) &= \frac{1}{3}r = \frac{1}{3} \times \frac{1}{3} = \frac{1}{9} \\

P(K = k_3) &= \frac{2}{3}r = \frac{2}{3} \times \frac{1}{3} = \frac{2}{9}\\

P(K = k_4) &= r = \frac{1}{3} \\

\end{align*}We can see that,

P(C = c \,|\, M = m) = P(K = k_0) + P(K = k_2) = P(K = k_1) + P(K = k_3) = P(K = k_4) = r = \frac{1}{3}for every c \in C \text{ and } m \in M.

The above equation shows that any message is transformed into any ciphertext by keys k_0 \text{ and } k_2 or keys k_1 \text{ and } k_3 or key k_4 with the same total probability r = \dfrac{1}{3}.

There are more keys than ciphertexts (the key space consists of 5 keys, while the ciphertext space’s cardinality is 3) since a message is transformed into a ciphertext by one or two keys, such that P(C = c \,|\, M = m) = r for every c \in C \text{ and } m \in M and all the keys transforming a particular message m into different c \text{'s} must be different.

Hence, |K| \geq |C|.

Relationship between |K| and |M|

We have already shown that any message in the message space enciphers to any ciphertext in the ciphertext space with equal and non-zero probability i.e., the value of P(C = c \,|\, M = m) is non-zero and the same for any c \in C \text{ and } m \in M.

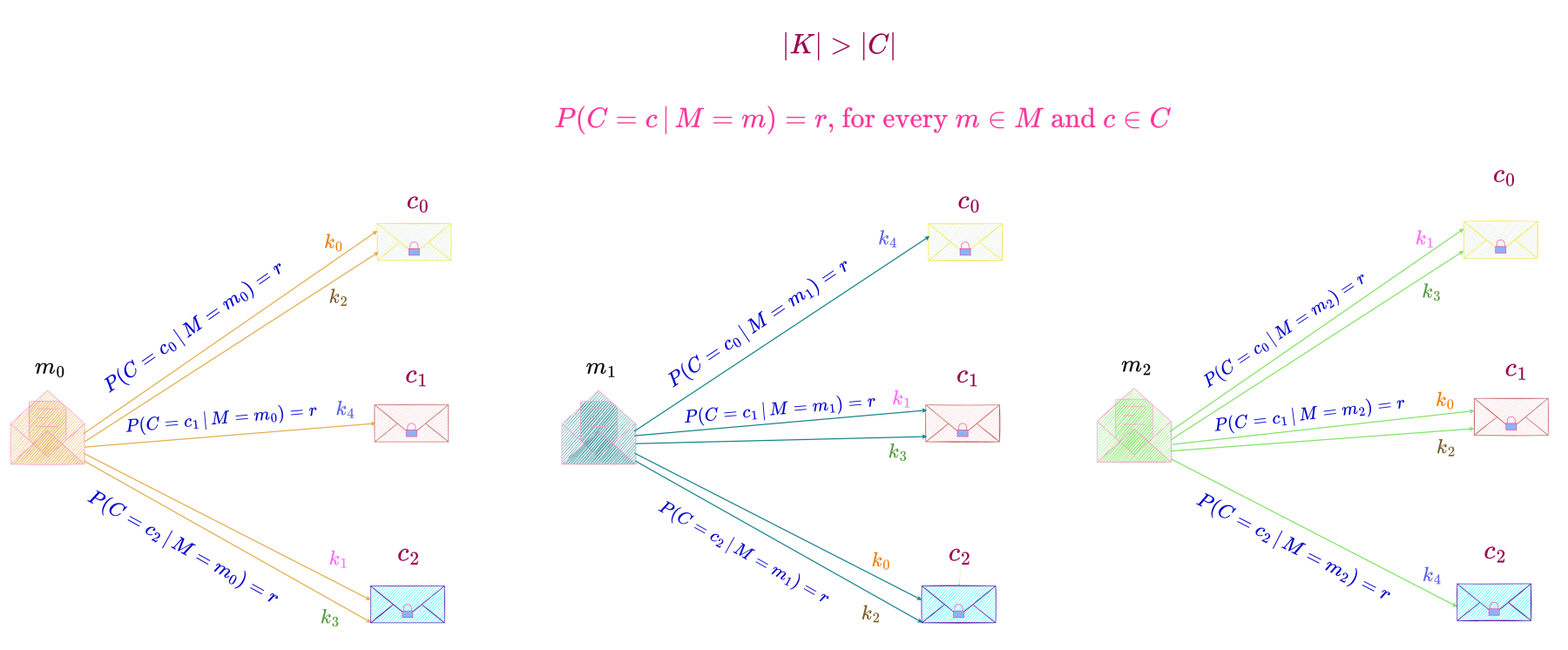

Below is an illustration of this result i.e., every message in the message space enciphering to every ciphertext in the ciphertext space with equal and non-zero probability, r.

Since P(C = c \,|\, M = m) = P(C = c) \neq 0 for any c \in C \text{ and any } m \in M, it must be the case that there is at least one key transforming any m into any of the possible c\text{'s}.

But all the keys transforming different messages into a particular ciphertext c must be different so that given a ciphertext and key unique decipherment is possible. Therefore, the number of keys is at least equal to the number of messages, i.e., |K| \geq |M|.

It should also be noted that since a key is first chosen and shared independent of the message that needs to be communicated, it means that a key should be able to encrypt any message in the message space. Hence every key in the key space can encipher any message in the message space.

These two cases, |K| = |M| \text{ and } |K| > |M| are illustrated below.

Let us next consider two examples of perfect secrecy systems one with |K| = |M| \text{ and other with } |K| > |M|.

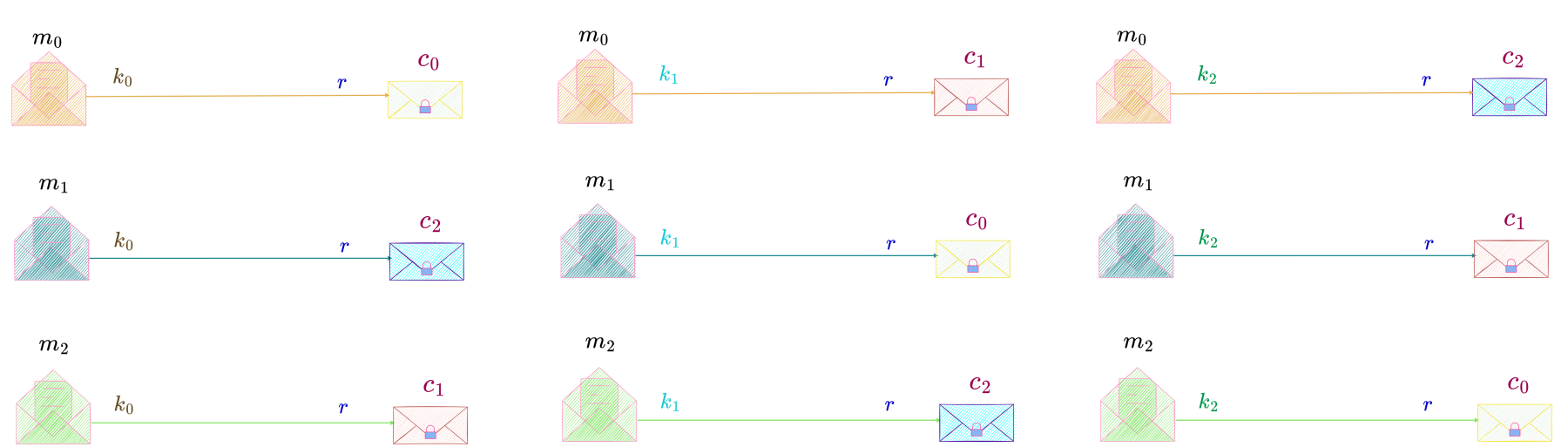

For the case |K| = |M|, we consider a perfect secrecy system with

M = \{m_0, m_1, m_2\}, K = \{k_0, k_1, k_2\} \text{ and } C = \{c_0, c_1, c_2\}, as shown below.

As we have already shown in the case where |K| = |C|,

\begin{equation*}

\begin{split}

P(C = c_0 \,|\, M = m_0) & = \sum_{k \,\in\, K} P(K = k)\, P(C = c_0 \,|\, M = m_0, K = k) \\

& = P(K = k_0)

\end{split}

\end{equation*}Similarly,

P(C = c_0 \,|\, M = m_1) = P(K = k_1)

and

P(C = c_0 \,|\, M = m_2) = P(K = k_2)

Since

P(C = c_0 \,|\, M = m_0) = P(C = c_0 \,|\, M = m_1) = P(C = c_0 \,|\, M = m_2)

it follows that,

P(K = k_0) = P(K = k_1)=P(K = k_2)

i.e., when |K| = |M|, the distribution of keys is uniform.

Since P(C = c_0 \,|\, M= m_0) = P(C = c_1 \,|\, M = m_0) = P(C = c_2 \,|\, M= m_0) = r, i.e., the total probability of all keys transforming the message to a particular ciphertext equals that of all keys transforming the same message to any other ciphertext and there is only one key transforming the message to a particular ciphertext, each key has an equal probability, r, of being picked.

For the case |K| > |M|,

we consider a perfect secrecy system with M = \{m_0, m_1, m_2\}, K = \{k_0, k_1, k_2, k_3, k_4\} \text{ and } C = \{c_0, c_1, c_2\}, as shown below.

As we have already shown in the case where |K| > |C|,

P(C = c \,|\, M = m) = P(K = k_0) + P(K = k_2) = P(K = k_1) + P(K = k_3) = P(K = k_4) = r = \frac{1}{3}for every c \in C \text{ and } m \in M.

The above equation shows that any message is transformed into any ciphertext by keys k_0 \text{ and } k_2 or keys k_1 \text{ and } k_3 or key k_4 with the same total probability r = \dfrac{1}{3}.

In this perfect secrecy system there are more keys than messages (the key space consists of 5 keys, while the message space’s cardinality is 3) because a message is transformed into a ciphertext by one or two keys, such that P(C = c \,|\, M = m) = r for every c \in C \text{ and } m \in M and all the keys transforming different messages m into a particular ciphertext c must be different so that given a ciphertext and key unique decipherment is possible.

Hence, |K| \geq |M|.

Relationship between |C| and |M|

Since any key in the key space enciphers every message in the message space to a different ciphertext such that given the ciphertext and key, unique decipherment is possible, there must be at least as many ciphertexts as there are messages i.e.,

|C| \geq |M|

We illustrate the two cases, namely, |C| = |M| \text{ and } |C| > |M| below.

Below is the illustration of a perfect secrecy system with |C| = |M|, where the message space consists of 3 messages, the key space consists of 3 keys and the ciphertext space also consists of 3 ciphertexts. The keys are drawn from a uniform distribution and the probability of choosing a key is \dfrac{1}{3}, i.e., r = \dfrac{1}{3}.

We can see that for any key in the key space there is a one-to-one correspondence between all the messages in the message space and all the ciphertexts in the ciphertext space.

Next let us explore the case when |C| > |M|.

From the two illustrations shown below depicting the cases |K| = |M| \text{ and } |K| > |M|, we can see that the entire key space is exhausted by all the messages that transform to a particular ciphertext i.e., every message in the message space transforms to a particular ciphertext through some permutation of the entire key space.

From the illustration on the left, where |K| = |M|, we can see that some permutation of the entire key space i.e., K = \{k_0, k_1, k_2\} transforms the message space i.e., M = \{m_0, m_1, m_2\} into a particular ciphertext, c.

Similarly, in the illustration on the right, where |K| > |M|, some permutation of the entire key space i.e., K = \{k_0, k_1, k_2, k_3, k_4\} transforms the message space i.e., M = \{m_0, m_1, m_2\} into a particular ciphertext, c.

However, in some cases when |K| > |M|, depending on the probability distribution of the keys, only a subset of the key space is exhausted (used) when the message space is transformed to a particular ciphertext as explained below.

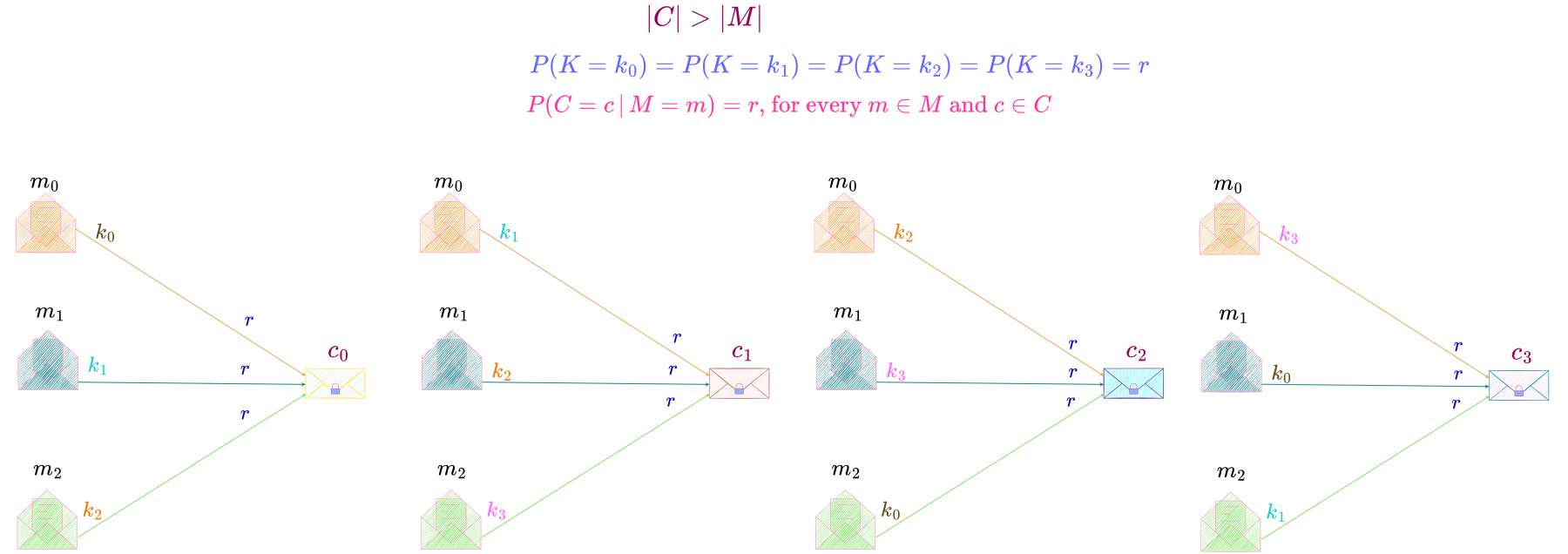

Consider a perfect secrecy system where the key space consists of 4 keys, all equally likely and the message space consists of only 3 messages.

In a perfect secrecy system, the probability that a message transforms to a particular ciphertext equals that of the message transforming to any other ciphertext in the ciphertext space. Since in this particular perfect secrecy system every key in the key space has an equal probability, r, of being picked, and every key in the key space can encipher any message in the message space, each key in the key space transforms a particular message into a unique ciphertext so that the probability of the message transforming to any ciphertext in the ciphertext space is the same and equals r. Hence, each of the 4 keys encipher a particular message into 4 different ciphertexts as shown below. Since each of the 3 messages in the message space are transformed into 4 different ciphertexts by 4 equally likely keys, in this case, |C| > |M|.

Since there are only 3 messages and each key is equally likely, there is only one unique key that transforms each of those messages into a particular ciphertext. Hence here only 3 out of the 4 keys are used to transform the message space into a particular ciphertext i.e., the entire key space is not used to transform the message space into a ciphertext. In the example shown above only keys k_0, k_1 \text{ and } k_2 are used to transform the 3 messages m_0, m_1 \text{ and } m_2 into ciphertext c_0.

Therefore, for every key in the key space, there is a one-to-one correspondence between all messages in the message space and some of the ciphertexts in the ciphertext space.

This case of |C| > |M| is illustrated below. Since the keys are drawn from a uniform distribution and there are four keys, r = \dfrac{1}{4}.

We can see from the above illustration that every message is enciphered by all the four keys (since a key should be able to encipher any message in the message space), but every ciphertext is not deciphered by all the keys (in fact only 3 keys decipher each ciphertext). So for any fixed key there is a one-to-one correspondence between all the messages in the message space, and some of the ciphertexts in the ciphertext space.

For example, for the key k_0, there is a one-to-one correspondence between the messages m_0, m_1 \text{ and } m_2 and the ciphertexts c_0, c_3 \text{ and } c_2 i.e., a one-to-one correspondence between all the 3 messages in the message space and 3 out of the 4 ciphertexts in the ciphertext space. This is a consequence of |K| > |M| and each key being equally likely i.e., the key space having a uniform distribution (and also the total probability of each message transforming to a particular ciphertext requiring to equal that of every other message transforming to the same ciphertext).

It should be noted that though all keys don’t decipher a particular ciphertext, a ciphertext still deciphers to every message in the message space with equal probability and also every message in the message space also enciphers to every ciphertext in the ciphertext space with equal probability. Hence perfect secrecy is still maintained.

So far we have proved that,

\begin{equation*}

\begin{split}

|K| & \geq |C| \\

|K| & \geq |M| \text{ and} \\

|C| & \geq |M| \\

\end{split}

\end{equation*}It follows from the above inequalities that,

|K| \geq |C| \geq |M|

As an aside, though we don’t need |K| \geq |M| to prove the above relationship, we needed it to prove |C| \geq |M|.

Various kinds of Perfect Secrecy Systems

Perfect Secrecy System with |K| > |C| > |M|

By axiom of probability,

\begin{equation*}

\begin{split}

P(C = c_0 \,|\, M = m_0) + P(C = c_1 \,|\, M = m_0) + P(C = c_2 \,|\, M = m_0)&= 1 \\

r + r + r &= 1\\

3r &= 1 \\

r &= \frac{1}{3}\\

\end{split}

\end{equation*}Also,

\begin{equation*}

\begin{split}

P(C = c) &= \sum_{m \,\in\, M} P(M = m)\, P(C = c \,|\, M = m) \\

&= \sum_{m \,\in\, M} P(M = m) \times r \\

&= r \sum_{m \,\in\, M} P(M = m) \\

&= r \\

\end{split}

\end{equation*}for every c \in C, since P(C = c \,|\, M = m) = r for every c \in C \text{ and } m \in M and by axiom of probability, \displaystyle \sum_{m \,\in\, M} P(M = m) = 1.

Therefore,

P(C = c \,|\, M = m) = P(C = c) = \frac{1}{3}for all c \in C \text{ and } m \in M.

Also,

\begin{equation*}

\begin{split}

P(C = c_0 \,|\, M = m_0) & = \sum_{k \,\in\, K} P(K = k)\, P(C = c_0 \,|\, M = m_0, K = k) \\

& = P(K = k_0)

\end{split}

\end{equation*}Similarly,

P(C = c_1 \,|\, M = m_0) = P(K = k_1)

and

P(C = c_2 \,|\, M = m_0) = P(K = k_2) + P(K = k_3)

Therefore,

P(K = k_0) = P(K = k_1) = r = \frac{1}{3}and

P(K = k_2) = P(K = k_3) = \frac{1}{2}r = \frac{1}{6}In this perfect secrecy system, each message is transformed to a particular ciphertext by one or two keys.

Also, for every key in the key space there is a one-to-one correspondence between all the messages in the message space and some of the ciphertexts in the ciphertext space. For example, for key k_0, there is a one-to-one correspondence between messages m_0 \text{ and } m_1 and ciphertexts c_0 \text{ and } c_1.

The distribution of keys is non-uniform.

Perfect Secrecy System with |K| > |C| = |M|

By axiom of probability,

\begin{equation*}

\begin{split}

P(C = c_0 \,|\, M = m_0) + P(C = c_1 \,|\, M = m_0) &= 1 \\

\frac{3}{2}r + \frac{3}{2}r &= 1\\

3r &= 1 \\

r &= \frac{1}{3}\\

\end{split}

\end{equation*}Also,

\begin{equation*}

\begin{split}

P(C = c) &= \sum_{m \,\in\, M} P(M = m)\, P(C = c \,|\, M = m) \\

&= \sum_{m \,\in\, M} P(M = m) \times \frac{3}{2}r \\

&= \frac{3}{2}r \sum_{m \,\in\, M} P(M = m) \\

&= \frac{3}{2}r \\

\end{split}

\end{equation*}for every c \in C, since P(C = c \,|\, M = m) = \dfrac{3}{2}r for every c \in C \text{ and } m \in M and by axiom of probability, \displaystyle \sum_{m \,\in\, M} P(M = m) = 1.

Therefore,

P(C = c \,|\, M = m) = P(C = c) = \frac{3}{2}r =\frac{1}{2}for all c \in C \text{ and } m \in M.

Also,

\begin{equation*}

\begin{split}

P(C = c_0 \,|\, M = m_0) & = \sum_{k \,\in\, K} P(K = k)\, P(C = c_0 \,|\, M = m_0, K = k) \\

& = P(K = k_0) + P(K = k_2) \\

\end{split}

\end{equation*}Similarly,

P(C = c_1 \,|\, M = m_0) = P(K = k_1) + P(K = k_3)

As can be seen from the above illustration,

P(K = k_0) = P(K = k_1) = r = \frac{1}{3}and

P(K = k_2) = P(K = k_3) = \frac{1}{2}r = \frac{1}{6}In this perfect secrecy system, each message is transformed to a particular ciphertext by exactly two keys.

Also, for every key in the key space there is a one-to-one correspondence between all the messages in the message space and all the ciphertexts in the ciphertext space.

The distribution of keys is non-uniform.

Perfect Secrecy System with |K| = |C| > |M|

By axiom of probability,

\begin{equation*}

\begin{split}

P(C = c_0 \,|\, M = m_0) + P(C = c_1 \,|\, M = m_0) + P(C = c_2 \,|\, M = m_0) + P(C = c_3 \,|\, M = m_0)&= 1 \\

r + r + r + r &= 1\\

4r &= 1 \\

r &= \frac{1}{4}\\

\end{split}

\end{equation*}Also,

\begin{equation*}

\begin{split}

P(C = c) &= \sum_{m \,\in\, M} P(M = m)\, P(C = c \,|\, M = m) \\

&= \sum_{m \,\in\, M} P(M = m) \times r \\

&= r \sum_{m \,\in\, M} P(M = m) \\

&= r \\

\end{split}

\end{equation*}for every c \in C, since P(C = c \,|\, M = m) = r for every c \in C \text{ and } m \in M and by axiom of probability, \displaystyle \sum_{m \,\in\, M} P(M = m) = 1.

Therefore,

P(C = c \,|\, M = m) = P(C = c) = \frac{1}{4}for all c \in C \text{ and } m \in M.

Also,

\begin{equation*}

\begin{split}

P(C = c_0 \,|\, M = m_0) & = \sum_{k \,\in\, K} P(K = k)\, P(C = c_0 \,|\, M = m_0, K = k) \\

& = P(K = k_0)

\end{split}

\end{equation*}Similarly,

\begin{equation*}

\begin{split}

P(C = c_1 \,|\, M = m_0) &= P(K = k_1), \\

P(C = c_2 \,|\, M = m_0) &= P(K = k_2)\& \\

P(C = c_3 \,|\, M = m_0)&= P(K = k_3) \\

\end{split}

\end{equation*}Therefore,

P(K = k_0) = P(K = k_1) = P(K = k_2) = P(K = k_3) = r = \frac{1}{4}In this perfect secrecy system, each message is transformed to a particular ciphertext by exactly one key. Hence, the distribution of keys is uniform.

Also, for every key in the key space there is a one-to-one correspondence between all the messages in the message space and some of the ciphertexts in the ciphertext space. For example, for key k_0, there is a one-to-one correspondence between messages m_0, m_1 \text{ and } m_2 and ciphertexts c_0, c_3 \text{ and } c_2.

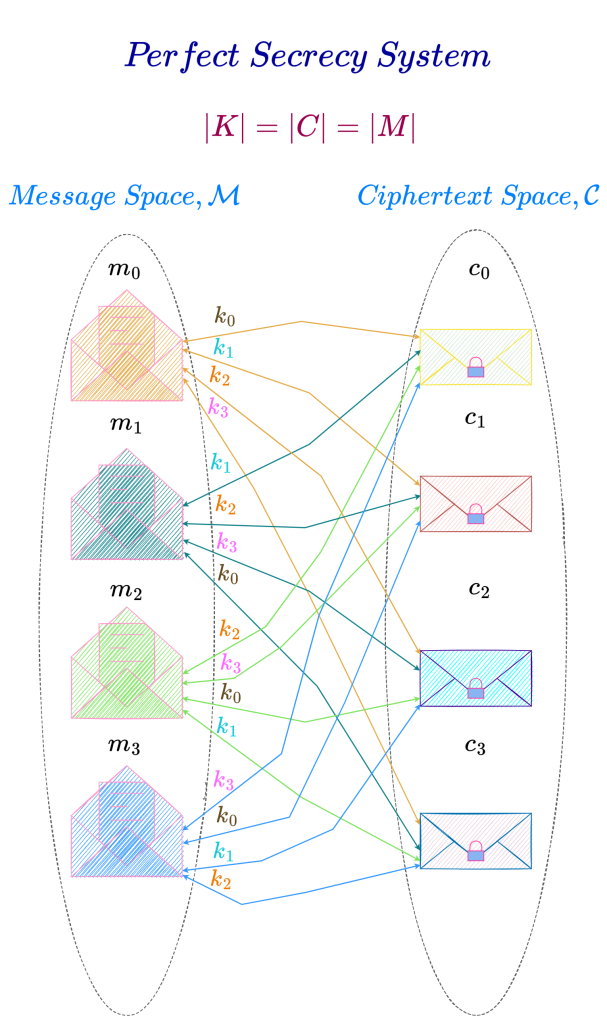

Perfect Secrecy System with |K| = |C| = |M|

By axiom of probability,

\begin{equation*}

\begin{split}

P(C = c_0 \,|\, M = m_0) + P(C = c_1 \,|\, M = m_0) + P(C = c_2 \,|\, M = m_0) + P(C = c_3 \,|\, M = m_0)&= 1 \\

r + r + r + r &= 1\\

4r &= 1 \\

r &= \frac{1}{4}\\

\end{split}

\end{equation*}Also,

\begin{equation*}

\begin{split}

P(C = c) &= \sum_{m \,\in\, M} P(M = m)\, P(C = c \,|\, M = m) \\

&= \sum_{m \,\in\, M} P(M = m) \times r \\

&= r \sum_{m \,\in\, M} P(M = m) \\

&= r \\

\end{split}

\end{equation*}for every c \in C, since P(C = c \,|\, M = m) = r for every c \in C \text{ and } m \in M and by axiom of probability, \displaystyle \sum_{m \,\in\, M} P(M = m) = 1.

Therefore,

P(C = c \,|\, M = m) = P(C = c) = \frac{1}{4}for all c \in C \text{ and } m \in M.

Also,

\begin{equation*}

\begin{split}

P(C = c_0 \,|\, M = m_0) & = \sum_{k \,\in\, K} P(K = k)\, P(C = c_0 \,|\, M = m_0, K = k) \\

& = P(K = k_0)

\end{split}

\end{equation*}Similarly,

\begin{equation*}

\begin{split}

P(C = c_1 \,|\, M = m_0) &= P(K = k_1), \\

P(C = c_2 \,|\, M = m_0) &= P(K = k_2)\& \\

P(C = c_3 \,|\, M = m_0)&= P(K = k_3) \\

\end{split}

\end{equation*}Therefore,

P(K = k_0) = P(K = k_1) = P(K = k_2) = P(K = k_3) = r = \frac{1}{4}In this perfect secrecy system, each message is transformed to a particular ciphertext by exactly one key. Hence, the distribution of keys is uniform.

Also, for every key in the key space there is a one-to-one correspondence between all the messages in the message space and all the ciphertexts in the ciphertext space. For example, for key k_0, there is a one-to-one correspondence between messages m_0, m_1, m_2 \text{ and } m_3 and ciphertexts c_0, c_3, c_2 \text{ and } c_1.

Perfect secrecy systems in which the number of keys, the number of messages and the number of ciphertexts are all equal are characterized by the following properties :

- Every message in the message space is transformed to a particular ciphertext in the ciphertext space by exactly one key.

- All the keys in the key space are equally likely.

Hence, from an implementation perspective the simplest (or easiest) possible perfect secrecy system to build is one in which the number of keys, the number of messages and the number of ciphertexts are all equal, i.e.,

|K| = |C| = |M|

Reusing keys makes a Perfect Secrecy System Insecure

Since a perfect secrecy system transforms a message into a ciphertext in a deterministic way i.e., the same message will always generate the same ciphertext for the same key, as we have already discussed, reusing the key to encipher more than one message will make the prefect secrecy system insecure.

The following example shows how a perfect secrecy system can become insecure if the same key is used to encipher more than one message.

Suppose Maria decides to lives between Paris and Milan during the next 100 days. She will spend 80\% of her time in Paris and the remaining 20\% in Milan i.e., 80 days in Paris and 20 days in Milan. Also, in every 10 days period she will spend between 1 \text{ to } 3 days in Milan and the remaining days in Paris. She would like to communicate her location to Bob every single day in secrecy so that no one else knows her whereabouts. They use a simple perfect secrecy system as detailed below.

Let us consider two scenarios, namely, one in which Maria shares a key with Bob only once and then reuses the same key to encipher her location and send it to Bob every time she communicates her location to him. In the other scenario, every time Maria wishes to communicate her location to Bob she picks a key at random from the key space and then encrypts the message (location) using that key. Let us analyze the security of the perfect secrecy system in both these scenarios.

In the first scenario, Maria meets Bob before leaving for Paris and shares key k_1 with him. Over the next 100 days she will use this key to encrypt her communication with Bob.

Following table shows her location for the first ten days, together with the ciphertext she sent to Bob each day to communicate her location to him encrypted using the shared key k_1.

Suppose an eavesdropper intercepts the communication between Maria and Bob and observes the ciphertexts. He will see that 7 days the location was encrypted to c_1 and 3 days to c_0. Suppose he is aware of the probability distribution of the message space i.e., Maria spending majority of the time in Paris, then observing that c_1 occurs more frequently than c_0 he will rightly deduce that ciphertext c_1 is the encryption of Paris and c_0 of Milan. Hence without even knowing the encryption key, he will be able to decipher the message and hence know where Maria will be each day by intercepting the ciphertext alone, thereby making the secrecy system useless.

Let us now consider an alternate scenario. Maria meets Bob each day and shares with him a key which she picks at random. Next day using this key, she encrypts her location and sends it to Bob and Bob meets her at that location.

Following table shows her location for the first ten days, together with the ciphertext she sent to Bob each day to communicate her location to him encrypted using the shared key k_0 \text{ or } k_1 which she picked at random with equal probability.

Suppose an eavesdropper observes the ciphertexts that Maria sends to Bob. He sees that on 6 days c_1 was sent and 4 days c_0 was sent. Since he is aware that Maria spends majority of her days in Paris, he assumes c_1 to be the encryption of Paris and c_0 Milan. Now suppose he decrypts under this assumption. Looking at the table, we can see that he will be right on days 1, 4, 7, 9 \text{ and } 10 and wrong on days 2, 3, 5, 6 \text{ and } 8 i.e., he is right on 5 days and wrong on 5 days, which is no better than making a random guess each day on Maria’s location. Even if he assumes the contrary, i.e., c_1 as the encryption of Milan and c_0 that of Paris, he will still be right only 50\% of the time. Hence, when the key is not reused the ciphertext reveals no information about the message.

Summary

Before proceeding further, we will summarize our discussion so far.

Necessary and Sufficient Condition for Perfect Secrecy

A necessary and sufficient condition for perfect secrecy is that

P(C = c \,|\,M = m) = P(C = c)

for all m \text{ and } c; i.e., the message and the ciphertext distributions are independent of each other.

Consequences of Perfect Secrecy

The necessary and sufficient condition for perfect secrecy i.e., the message and the ciphertext distribution being independent of one another, gives rise to the following consequences :

- The distribution of ciphertexts is uniform.

- Any message in the message space enciphers to any ciphertext in the ciphertext space with equal and non-zero probability i.e., the value of P(C = c \,|\, M = m) is non-zero and the same for any c \in C \text{ and } m \in M.

- The size (or cardinality) of the key space, K, must at least equal that of the ciphertext space, C, i.e., |K| \geq |C|.

- The cardinality of the key space must at least equal that of the message space i.e., |K| \geq |M|.

- The cardinality of the ciphertext space must at least equal that of the message space i.e., |C| \geq |M|.

- From 3 \text{ and } 5, we can see that |K| \geq |C| \geq |M|.

Practical Implementation of a Perfect Secrecy System

Now that we have discussed in depth the various criteria for secrecy systems to be perfectly secure, let us next proceed to an implementation of a perfect secrecy system. One example of a practical perfect secrecy system is a one-time pad which we will cover in depth in the following section.

To be continued…