authored by Premmi and Beguène

Previous Topic: An Axiomatic Study of Numbers

Introduction

Thinking of numbers intuitively brings to mind the simplest and most fundamental set of numbers, namely the set of natural numbers. These are the numbers we first encounter when learning to count discrete objects like cars, books, pens, etc. If we associate natural numbers such as 0, 1, 2, 3, etc., with this basic act of enumeration, then with what corresponding concepts do we relate numbers like -4, \sqrt{3} \text{ and } \frac{22}{7}?

To reason rigorously about the diverse kinds of numbers encountered in mathematics, we require a precise mathematical framework for their definition. We will construct this framework by first defining the natural numbers axiomatically within a chosen logical system, namely second-order logic, due to its greater expressive power. Unlike first-order logic, which is limited to making statements about individual numbers, second-order logic allows us to make more general statements by also enabling quantification over sets of numbers and the properties that these numbers can have. This richer expressive capability of second-order logic is essential for formulating a comprehensive axiom of induction (which we will state precisely in a subsequent section). This axiom plays a key role in characterizing the set of natural numbers within the Peano axiomatic system. Consequently, the use of second-order logic provides a more direct way to capture the fundamental nature of the natural numbers through our axiomatic system.

This axiomatic system of natural numbers, constructed by assuming some fundamental statements about natural numbers to be true without proof, serves as a foundation from which all other properties and theorems about natural numbers can be logically deduced. By adopting this axiomatic approach, independent of the intuitive notion of counting, we aim to formulate the natural numbers based on a minimal set of core assumptions. This rigorously defined foundation will then equip us to construct the subsequent number systems: integers, rational numbers, real numbers, and complex numbers, all derived from these foundational natural numbers.

The hallmark of a powerful axiomatic system is its ability to assume a minimal set of fundamental axioms while enabling the derivation of a maximal body of knowledge. To create an efficient axiomatization for the natural numbers, we must distill these numbers to their most essential properties. Intuitively, we understand various aspects of the natural numbers, such as their existence and the basic properties of the binary operations addition, multiplication, and the ‘less than’ order relation. How few of these concepts can we take as axioms, from which we can deduce everything else that we need to know about the natural numbers? It turns out that remarkably little is required for the axiomatization of the natural numbers—neither addition, nor multiplication, nor the ‘less than’ relation need to be taken as axioms; these will all be constructed from our fundamental axioms.

The standard axiomatization of the natural numbers, known as the Peano Axioms, was originally formulated by the Italian mathematician, Giuseppe Peano. In 1889, Peano’s seminal work, “Arithmetices principia, nova methodo exposita” (The principles of arithmetic, presented by a new method) laid the groundwork for the rigorous development of the real number system based on a set of axioms for the natural numbers. His presentation featured nine axioms, four of which established the properties of the equality relation “=” with regard to natural numbers and the remaining five axioms provided a complete and rigorous definition of the natural numbers.

To truly appreciate the intellectual feat of Peano, it’s worth noting that utilizing only his fundamental axioms we gain the deductive power to define and prove the operations on natural numbers together with all their established properties. Furthermore, these axioms provide the essential scaffolding that facilitates the rigorous construction of the integer, rational, real, and complex number systems.

Before we discuss Peano’s Axioms in detail, it is a useful exercise to explore an alternative way to describe natural numbers, distinct from the usual intuitive notion of counting. Such an investigation would help us to independently arrive at Peano’s axioms.

Intuition behind the Axiomatic Definition of Natural Numbers

How do we model the concept of natural numbers denoted by 0, 1, 2, 3 and so on without relying on the notion of counting?

The way we count, starting from 0 and progressing sequentially to 1, then 2, and so on, reveals the core characteristic of natural numbers: a sequential structure where each subsequent number follows uniquely from the previous, beginning with 0. This is what we aim to formalize in our axiomatic definition.

Recognizing that the natural numbers constitute a collection with a sequential structure, which mathematical object is best suited to represent such a collection?

A set, with its capacity to contain elements and have relationships defined among them, provides the ideal structure for representing such a collection. Therefore, we will adopt a set-theoretic approach to define the natural numbers. This involves systematically enumerating the fundamental properties the set of natural numbers must have and meticulously describing the various relationships among its members, thereby, leading to the set \{0, 1, 2, 3, \ldots\}.

Having articulated our approach, we now proceed with the concrete steps of defining the set of natural numbers.

Let us denote the set of natural numbers as \mathcal{N}. First, we recognize that 0 should be a part of this set. Next, we want 0 to lead us to 1, 1 to 2 and we should be able to continue this way, naming each successive number as far as we wish. This is illustrated below.

0 \rightarrow1 \rightarrow 2 \rightarrow 3 \rightarrow \ldots

From the above diagram we can see that to model this relationship we need a “next” operation that given a natural number, produces the next natural number in the sequence.

The above diagram can also be viewed as shown below.

\begin{equation*}

\begin{split}

0 &\rightarrow 1 \\

1 &\rightarrow 2 \\

2 &\rightarrow 3 \\

\vdots &\quad\,\,\,\, \vdots \\

\end{split}

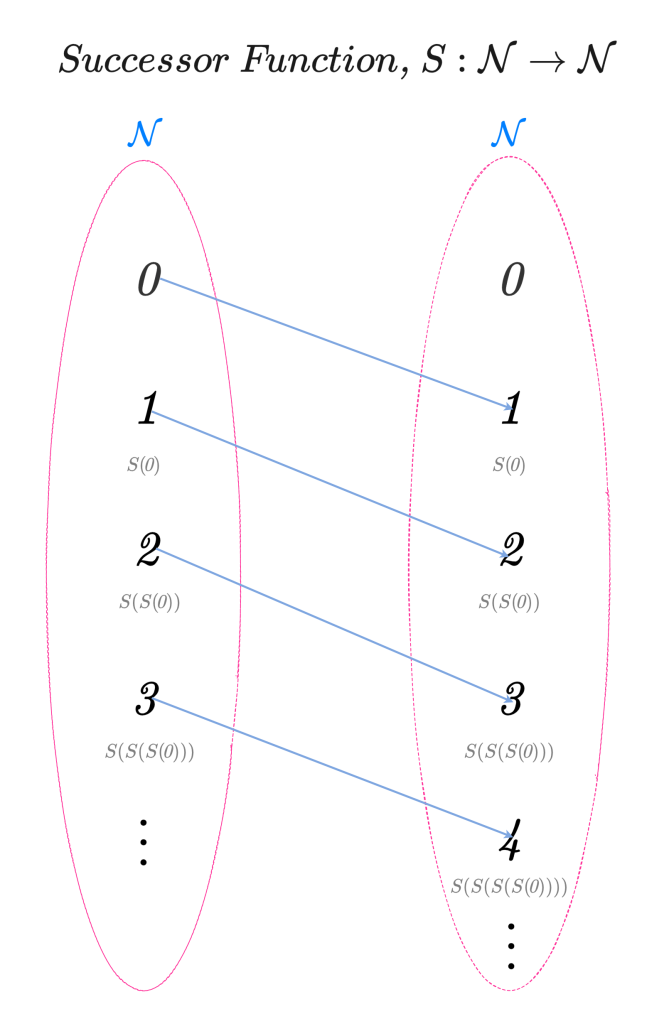

\end{equation*} We can see from the diagram that an input of 0 maps to an output of 1, an input of 1 maps to 2 and so on. Therefore, we can model the “next” operation as a function S : \mathcal{N} \rightarrow \mathcal{N} that takes a natural number as input and produces a natural number as output. Here, the letter S stands for ‘successor’ and we have S(0) = 1, S(1) = 2 and so forth. We will refer to this function S as the successor function since it establishes a succession within the set of natural numbers, \mathcal{N}. This function S is illustrated below.

From the diagram above, we can observe that the successor function S has the following properties, which intuitively align with our understanding of counting:

- Not Surjective: There is no natural number in \mathcal{N} that, when given as input to the successor function S, results in 0 as output. This implies that not every element of the codomain of S is the image of at least one element from its domain. Therefore, we can conclude that S is not surjective because S(n) \neq 0 \text{ for any } n \in \mathcal{N}.

Intuitively, this makes sense because we start counting from 0; therefore0 does not follow any other natural number in the standard counting sequence. - Injective: Different inputs to S yield different outputs. This means that every element of the codomain of S is the image of at most one element from its domain; that is, S(m) = S(n) \text{ implies that } m = n \text{ for any } n, m \in \mathcal{N}. Hence, S is injective.

This reflects the idea that when we count each number has a unique ‘next’ number; 1 follows 0 and no other number immediately follows 0 other than 1. Consequently, this ensures that the natural sequential order of the natural numbers is maintained where each number starting from 0 is followed by a unique number that is different from all the previous numbers, thus preventing the sequence from branching, merging or forming cycles in unexpected ways.

From the diagram, we can also see that a natural number is either 0 or can be obtained from 0 by applying the successor function to 0 a finite number of times. This highlights the fundamental way we generate all natural numbers; we start at 0 and keep going to the ‘next’ number. This process should give us all the natural numbers and nothing else. This implies that \mathcal{N} is the minimal non-empty set that contains 0 and admits a successor function satisfying conditions (1) \text{ and } (2) i.e., S is not surjective and is injective.

Therefore, for the Peano Axioms to accurately describe the set of natural numbers, they must define a set that contains 0 and supports a successor function as described above.

So far we have developed an intuitive understanding of how to define natural numbers axiomatically. Now we will turn our attention to how Giuseppe Peano originally formulated these axioms and the historical backdrop against which he developed his axioms, a period marked by a growing emphasis on logical rigor and the desire to provide firm foundations for mathematics.

Original Formulation of Peano’s Axioms: A Historical Context

Before we delve into the modern version of Peano’s Axioms, it is interesting to understand the intellectual landscape that gave rise to them. The late 19th century was a pivotal era in mathematics, marked by a burgeoning quest for logical rigor. This quest drove mathematicians to formalize arithmetic, transcending the limitations of purely intuitive apprehension to erect a more logically sound edifice.

Hermann Grassmann’s work in the 1860s demonstrated that many familiar truths of arithmetic could be built upon a more elementary foundation consisting of the successor function (the idea that each natural number has a unique “next” number) and mathematical induction (a method of proving statements about all natural numbers by first showing it’s true for the starting number (usually 0), and then showing that if it’s true for any number, it must also be true for the next one). Following this groundbreaking work, Charles Sanders Peirce provided an early axiomatization of natural-number arithmetic in 1881, and Richard Dedekind proposed another influential axiomatization in his 1888 publication, “Was sind und was sollen die Zahlen?” (What are numbers and what are they good for?), notably including the number 1 and the successor function as fundamental concepts.

Building upon these preceding efforts, Giuseppe Peano published his own streamlined and influential collection of axioms for the natural numbers in 1889 in his book Arithmetices principia, nova methodo exposita (The principles of arithmetic, presented by a new method). While Peano’s work drew inspiration from Dedekind’s, Peano’s formulation is now the accepted standard for the axiomatic definition of natural numbers.

Two years later, in 1891, Peano further refined his axiomatic system of natural numbers in his article ‘Sul concetto di numero’ (‘On the Concept of Number’), published in Rivista di Matematica, a journal he himself founded that same year. In this influential article, Peano reduced his list of axioms from nine to five. This simplification arose from the recognition that the fundamental properties of the equality relation ‘=’ such as reflexivity, symmetry, transitivity, and substitutivity are often considered integral to the underlying logical framework within which mathematical reasoning unfolds and are not specific to the definition of the natural numbers themselves, thereby exemplifying the inherent drive towards elegance and minimality in mathematical formalization. Therefore, for a more focused set of axioms uniquely characterizing the natural numbers, Peano chose to omit these axioms of equality.

Peano’s endeavor to formalize the natural numbers, while seemingly straightforward today, was a significant step in addressing the limitations of informal mathematical reasoning. Without a rigorous axiomatic system (a set of fundamental statements, called axioms, that are assumed to be true and from which all other statements are logically derived), proofs could be predicated on intuition that might not always hold, especially when constructing more intricate mathematical structures.

Peano was quite deliberate in using specific symbols for logical connectives and quantifiers that were distinct from the mathematical symbols representing numbers, operations, and sets. This practice of maintaining a clear separation between mathematical and logical symbols was innovative for his time and built upon earlier work by figures like Gottlob Frege (though Peano was initially unaware of Frege’s work). This constituted a move towards a more formal and unambiguous language for mathematics. Before this, mathematical writing often commingled these concepts more informally within prose.

While perusing Peano’s Axioms it is worth keeping in mind that during Peano’s time, the concept of set was still nascent; it was Peano who introduced the symbol \in in 1889 to denote “is an element of”. Being aware of Peano’s original formulation of these axioms helps us appreciate the subsequent trajectory of mathematical development and underscores that our pursuit of more refined mathematical notation and more powerful abstraction remains ongoing. 😃

The culmination of these foundational inquiries, as articulated in Peano’s seminal 1891 article “Sul concetto di numero” comprises the following five axioms which can be found within the pages 387-408 of the book “Historia Mathematica 1”, published in the year 1974:

We can see how the archaic notation obfuscates these axioms.

The interpretations of these axioms as stated in the same book “Historia Mathematica 1” are as follows:

For improved readability, these five axioms are presented below using LaTeX notation, accompanied by interpretations that elucidate their formal meaning within the axiomatic system:

(1) \quad\hspace{0.6em} 1 \hspace{0.7em} \varepsilon \hspace{0.7em} \mathit{N}

Interpretations:

- From “Historia Mathematica 1”: One is a number.

- Formal Interpretation: The element ‘one’ belongs to the collection of natural numbers, denoted by \mathit{N}.

(2) \quad\hspace{0.2em} + \hspace{0.35em} \varepsilon \hspace{0.6em} \mathit{N} \setminus \!\mathit{N} \quad

Interpretations:

- From “Historia Mathematica 1”: The sign + placed after a number produces a number.

- Formal Interpretation: The successor function, denoted by the postfixed symbol ‘+\text{'}, when applied to an element of the collection of natural numbers (\mathit{N}), yields an element that is also a member of the collection of natural numbers (\mathit{N}).

(3) \quad\hspace{0.5em} a, \hspace{0.7em} b \hspace{0.8em} \varepsilon \hspace{0.7em} \mathit{N} \hspace{0.7em} . \hspace{0.7em} a+ \hspace{0.35em} = \hspace{0.35em} b+ \hspace {0.7em}: \hspace{0.35em} \supset \hspace{0.35em}.\hspace{0.7em} a \hspace{0.35em}=\hspace{0.35em} b \quad

Interpretations:

- From “Historia Mathematica 1”: If a and b are two numbers, and if their successors are equal, then they are also equal.

- Formal Interpretation: For any two elements a and b that belong to the collection of natural numbers (\mathit{N}), if the successor of a\, (a+) is equal to the successor of b\, (b+), then a must be equal to b.

(4) \quad\hspace{0.5em} 1 \hspace{0.2em}- \hspace{0.2em} \varepsilon \hspace{0.6em} \mathit{N}+ \quad

Interpretations:

- From “Historia Mathematica 1”: One is not the successor of any number.

- Formal Interpretation: The element ‘one’ is not in the collection of successors of the elements in the collection of natural numbers (\mathit{N}).

(5) \quad\hspace{0.5em} s \hspace{0.5em} \varepsilon \hspace{0.5em} \mathit{K} \hspace{0.7em} . \hspace{0.7em} 1 \hspace{0.5em} \varepsilon \hspace{0.5em} s \hspace{0.7em} . \hspace{0.7em} s+ \hspace{0.35em} \supset \hspace{0.35em} s \hspace {0.7em}: \hspace{0.35em} \supset \hspace{0.35em}.\hspace{0.7em} \mathit{N} \hspace{0.35em} \supset \hspace{0.35em} s \quad

Interpretations:

- From “Historia Mathematica 1”: If s is a class containing one, and if the class made up of the successors of s is contained in s, then every number is contained in the class s.

- Formal Interpretation: For any class s belonging to the domain of classes (\mathit{K}), if ‘one’ is an element of s, and if the collection of successors of the elements in s\, (s+) is contained in s (meaning every element in s+ is also in s), then the collection of natural numbers (\mathit{N}) is contained in the class s (meaning every element in \mathit{N} is also in s).

Since axiom (5), as stated, can seem a bit convoluted, let’s break down its key components to facilitate understanding.

- s is a class belonging to the domain of classes (\mathit{K}) (s \,\varepsilon\, \mathit{K}): In Peano’s time, the distinction between “set” and “class” was not as rigorously defined as it became later with the development of axiomatic set theory (like ZFC). However, in this context, “class” generally refers to a collection of mathematical objects that share a certain property. We can think of it as being very similar to the modern idea of a set.

In summary, “s \,\varepsilon\, \mathit{K}" tells us that s is a collection (a class, similar to a set) of entities within Peano’s mathematical framework, and \mathit{K} is the universe of all such collections he was considering. So, this part just establishes that “s" is a valid collection within Peano’s system. In the context of axiom (5),\,s is a class that we are examining to see if it contains all the natural numbers. - s is a class containing one (1 \,\varepsilon\, s): We begin with the knowledge that the number 1 possesses the property defined by the class s.

- The class made up of the successors of s\, (s+ = \{x\!+ |\, x \in s\}) is contained in s\, (s+ \subset s): This part states that if we take all the elements currently in the class s and consider their successors, those successors are also guaranteed to be within the class s.

Let’s trace this informally:

\star\, We start with 1 \in s.

\star\, Since 1 \in s, its successor 1+ = 2 must be an element of s+ (the class of successors of s)

\star\, Because s+ \subset s, it follows that 2 is also an element of s.

\star\, Now, since 2 \in s, its successor 2+ = 3 must be an element of s+.

\star\, Again, because s+ \subset s, it follows that 3 is also an element of s.

\star\, This chain of reasoning continues indefinitely. If any natural number x is in s, its successor x+ will be in s+, and therefore also in s due to the containment s+ \subset s. - Then every number is contained in the class s\, (\mathit{N} \subset s): This is the conclusion. If the class s contains 1 \hspace{2em}and has the property that the successor of any element in s is also in s, then the class s must contain all the natural numbers.

This axiom might appear somewhat complex, but it plays a crucial role in defining the collection of natural numbers, \mathit{N}. While the first four axioms guarantee that \mathit{N} contains at least the standard natural numbers \{1, 2, 3, \ldots\} (generated by starting with 1 and repeatedly applying the successor function), these axioms alone do not preclude the existence of additional ‘extra’ elements beyond this standard sequence, a possibility we will explore further when discussing Peano’s fifth axiom.. It is the power of axiom (5) that excludes such a possibility. This axiom is key to ensuring that the collection of natural numbers \mathit{N} contains only the standard sequence generated by starting with 1 and repeatedly applying the successor function, i.e., \mathit{N} = \{1, 2, 3, \ldots\}. By requiring that any class s containing 1 and closed under the successor operation (i.e., if x \in s, then x+ \in s) must contain all natural numbers, axiom (5) effectively excludes any ‘extra’ elements that are not reachable through this fundamental iterative process. This is because the class s = \{1, 2, 3, \ldots\} inherently contains 1 and is closed under the successor operation, thus always satisfying the axiom’s premise. This leads to the axiom’s conclusion that \mathit{N} must be contained in s, which is only possible when \mathit{N} = \{1, 2, 3, \ldots\}.

In the Peano Axioms published in 1889 \text{ and } 1891, the sequence of natural numbers began with 1, and the class of natural numbers was denoted by \mathit{N}. However, in 1898 these axioms were modified so that the sequence began with 0 and the class was denoted by \mathit{N_{\!0}}.

Peano’s decision to include 0 as the starting natural number likely stemmed from a growing recognition of its utility in emerging areas of mathematics, such as the elegant representation of the empty set’s cardinality as 0 within set theory, and in providing a more consistent basis for arithmetic and logical systems he was developing. Although specific examples of instances that directly motivated this shift might not be explicitly documented in readily available historical texts, this seemingly small change had a significant impact. It ultimately simplified and unified concepts across various mathematical fields, including algebra, leading to its widespread adoption as the standard.

The set of five Peano Axioms was increased to six in 1901 with the addition of the axiom – \mathit{N_{\!0}} \in \text{Cls}, i.e., the natural numbers form a class. With the addition of this last axiom, the axioms have received their final form, which are listed below.

The final form of the six axioms of Peano presented in LaTeX along with their interpretations are as follows:

(0) \quad\hspace{0.6em} \mathit{N_0} \hspace{0.7em} \varepsilon \hspace{0.7em} \textit{Cls} \quad

Formal Interpretation: The natural numbers form a class.

(1) \quad\hspace{0.6em} \mathit{0} \hspace{0.7em} \varepsilon \hspace{0.7em} \mathit{N_0} \quad

Formal Interpretation: Zero belongs to the class of natural numbers.

(2) \quad\hspace{0.5em} a \hspace{0.8em} \varepsilon \hspace{0.7em} \mathit{N_0} \hspace{0.9em} . \hspace{0.35em} \supset \hspace{0.35em} . \hspace{0.9em} a+ \hspace {0.5em}\varepsilon \hspace{0.7em} \mathit{N_0} \quad

Formal Interpretation: If a belongs to the class of natural numbers, then its successor (a+) also belongs to the class of natural numbers.

(3) \quad\hspace{0.5em} s \hspace{0.5em} \varepsilon \hspace{0.5em} \textit{Cls} \hspace{0.7em} . \hspace{0.7em} \mathit{0} \hspace{0.7em} \varepsilon \hspace{0.7em} s \hspace{0.7em} : \hspace{0.7em} x \hspace{0.7em} \varepsilon \hspace{0.7em} s \hspace {0.7em}. \hspace{0.35em} \supset_{\normalsize \,x} \hspace{0.35em}.\hspace{0.7em} x+\!\! \hspace{0.7em} \varepsilon \hspace{0.7em} s \hspace {0.7em}: \hspace{0.35em} \supset \hspace{0.35em}.\hspace{0.7em}\mathit{N_0} \hspace{0.35em} \supset \hspace{0.35em} s \quad

Formal Interpretation: If s is a class containing zero, and if for every element x in s, its successor (x+) is also in s, then the class of natural numbers \mathit{N_0} is contained in the class s (meaning every element in \mathit{N_0} is also in s).

(4) \quad\hspace{0.5em} a, \hspace{0.7em} b \hspace{0.8em} \varepsilon \hspace{0.7em} \mathit{N_0} \hspace{0.7em} . \hspace{0.7em} a \hspace{0.35em}+ \hspace{0.35em} 1 \hspace{0.35em} = \hspace{0.35em} b \hspace{0.35em} + 1 \hspace {0.7em}. \hspace{0.35em} \supset \hspace{0.35em}.\hspace{0.7em} a \hspace{0.35em}=\hspace{0.35em} b \quad

Formal Interpretation: If a and b belong to the class of natural numbers and the successor of a\, (a + 1) is equal to the successor of b\, (b + 1), then a and b must be equal.

(5) \quad\hspace{0.5em} a \hspace{0.8em} \varepsilon \hspace{0.7em} \mathit{N_0} \hspace{0.9em} . \hspace{0.35em} \supset \hspace{0.35em} . \hspace{0.9em} a \hspace {0.5em} + \hspace{0.5em} 1 \hspace{0.5em} - \hspace{0.5em} = \hspace{0.5em} \mathit{0}\quad

Formal Interpretation: If a belongs to the class of natural numbers then its successor a + 1 is not equal to 0 (meaning zero is not the successor of any natural number).

We can see that the key changes between the original five axioms and the final six are as follows:

- the explicit statement that the natural numbers form a class which reflects a move towards greater formalization within Peano’s system

- the inclusion of 0 as the starting natural number

- consequently, the axiom 3 (originally listed as axiom 5) now begins with the condition that 0 belongs to the class s

With this historical backdrop in mind, let us now examine the axioms themselves and their role in the formal definition of natural numbers.

The Axiomatization of Natural Numbers

We will first define the notion of equality as it pertains to natural numbers, and then we will formulate the Peano Axioms such that it provides an axiomatic definition of natural numbers.

As discussed in the historical context section, the concept of equality extends beyond natural numbers to mathematical objects in general and pertains more to the realm of logic, which specifies the conditions under which two mathematical objects can be considered equal. This likely explains Peano’s decision to omit the formal axioms of equality from his later formulation concerning only the natural numbers.

Although Giuseppe Peano omitted the four axioms related to the equality relation from his later formulation of the axioms regarding natural numbers, we will still discuss these axioms for the sake of completeness.

In our discussion of Peano’s Axioms, we will adopt some conventions from its final form. Therefore, we will start with 0 instead of 1 in our axiomatic system and denote the set of natural numbers by \mathbb{N_0}, where the subscript 0 reminds us that 0 is included.

The Notion of Equality

Before we define the set of natural numbers \mathbb{N_0} axiomatically, we will formalize the notion of equality through the four axioms of Peano, which establish the properties that the equality relation, denoted by =, must satisfy.

Suppose there exists a set \mathbb{N_0} that satisfies Axioms 1 t0 9 listed below.

Firstly, every natural number should be equal to itself; this is called the reflexivity axiom.

Axiom \mathbf{1}. For every x \in \mathbb{N_0}, x = x.

Secondly, if one natural number equals a second one, then the second one should equal the first one. This is known as the symmetry axiom.

Axiom \mathbf{2}. For every x, y \in \mathbb{N_0}, \text{ if } x = y, \text{ then } y = x.

Thirdly, if one natural number is equal to a second, and that second natural number is equal to a third, then the first and third are equal to each other. This is called the transitivity axiom.

Axiom \mathbf{3}. For every x, y, z \in \mathbb{N_0}, \text{ if } x = y \text{ and } y = z, \text{ then } x = z.

These three properties—reflexivity (pertaining to a single object), symmetry (pertaining to two objects), and transitivity (pertaining to three objects)—are fundamental characteristics of the equality relation as it applies to any type of mathematical objects. As we have already discussed during our study of Set Theory, equality is an example of an equivalence relation, which is a type of homogeneous binary relation that satisfies these three properties.

Since the equality relation is defined generically for all mathematical objects and not just for natural numbers, we must make explicit the assumption that if two mathematical objects are equal (i.e., they satisfy the equality relation) and one of them is a natural number, then the other must also be a natural number. The next axiom makes this assumption explicit, namely, a natural number can only be equal to another natural number.

Fourthly, if any mathematical object is equal to a natural number, then that mathematical object is itself a natural number. This is called the closure of equality axiom.

Axiom \mathbf{4}. For all x \text{ and } y, \text{ if } x \in \mathbb{N_0} \text{ and } x = y, \text{ then } y \in \mathbb{N_0}.

That is, the set of natural numbers is closed under equality.

The Peano Axioms

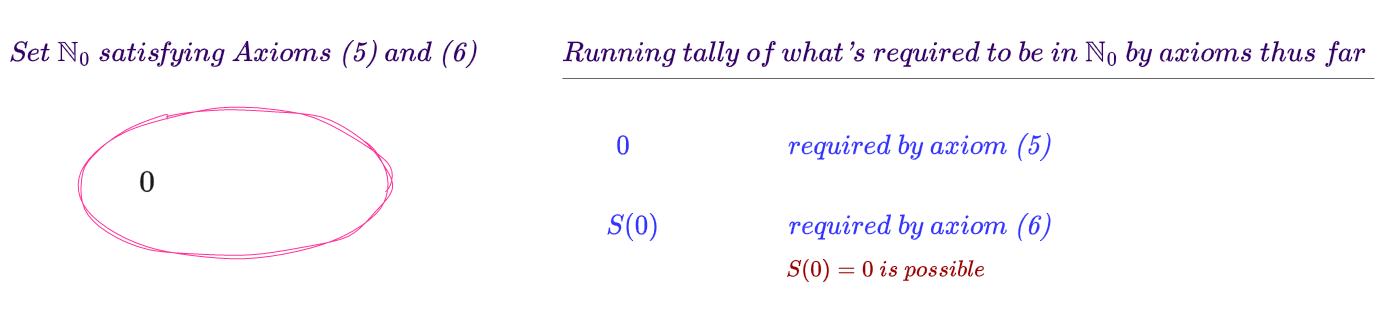

We will now discuss the five main Peano axioms that define the natural numbers. Peano aimed to formulate these axioms such that the fewest possible axioms could generate all the natural numbers. Therefore, we will construct the Peano axioms by checking, after stating each axiom, whether the axioms stated thus far can unambiguously result in the set of natural numbers that we know of. That is, we will continue constructing the Peano axioms until these axioms, when taken together, incontrovertibly result in \mathbb{N}_0 = \{0, 1, 2, \ldots\}.

This method of constructing the Peano axioms leads to the insight that the entire set of natural numbers can be generated by asserting the existence of at least one natural number and then defining a function called the successor function. This function takes a natural number as input and outputs another natural number, resulting in the construction of all remaining natural numbers.

Let us now proceed with the construction of the Peano Axioms.

Since we start counting from 0, it is unsurprising that 0 is the most obvious element to axiomatically include in the set of natural numbers.

Fifthly, 0 is a natural number.

Axiom \mathbf{5}. 0 \in \mathbb{N_0}.

Thus far we are only guaranteed the existence of a single natural number, 0.

From 0 we should be able to generate the other natural numbers; that is starting with 0 we should be able to reach 1, from 1 reach 2 and so on, akin to counting. We can model this progression from one natural number to the next using a function that takes a natural number as input and produces another natural number as output. This function is called the successor function since it establishes a succession within the set of natural numbers and is written as S : \mathbb{N_0} \rightarrow \mathbb{N_0}. The next axiom simply states that there is a function S whose domain and codomain are the set of natural numbers, \mathbb{N}_0.

Sixthly, every natural number has a successor which is also a natural number.

Axiom \mathbf{6}. If x \in \mathbb{N}_0, then S(x) \in \mathbb{N}_0.

That is, the set of natural numbers, \mathbb{N}_0, is closed under the successor operation, S.

As this axiom implies, we will refer to S(x) as the successor of \mathit{x}.

Till now we have only established that the set of natural numbers contains 0 and its successor, S(0), where the function S takes natural numbers as input and outputs natural numbers. However, we are still quite far from having the set of natural numbers that we know of, since we could have \mathbb{N}_0 = \{0\} and define S(0) = 0, which would still satisfy all of the above axioms. In this case, \mathbb{N}_0 = \{0\}, but we want \mathbb{N}_0 = \{0, 1, 2, 3, \ldots\}.

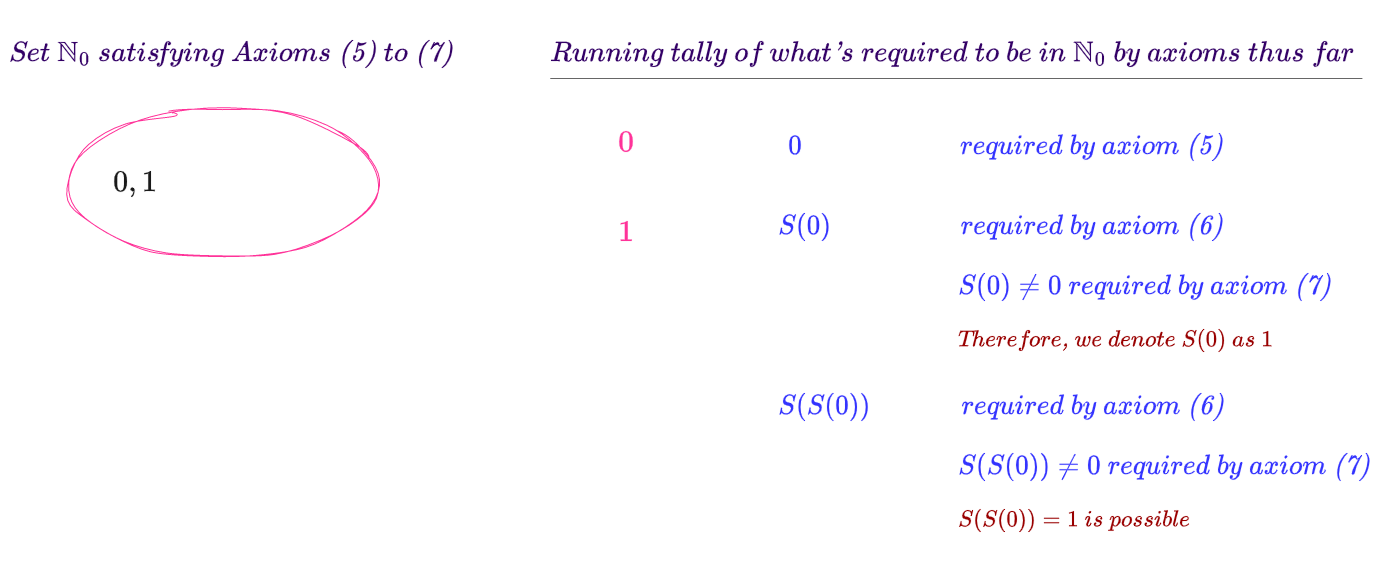

To achieve this, we need to ensure that the successor function S does not output 0 for any natural number input, because if it did, it could lead to cycles or a finite set, thus, preventing us from generating the infinite sequence of distinct natural numbers we expect. Our next axiom will guarantee this by forbidding 0 from being the successor of any natural number, including itself.

Seventhly, 0 is not the successor of any natural number.

Axiom \mathbf{7}. For every natural number x \in \mathbb{N}_0, S(x) \neq 0.

That means that there is no natural number whose successor is 0. Consequently, the preimage of 0 under S defined on the set of natural numbers is an empty set.

As a consequence of this axiom, we know that S(0) \neq 0. Therefore, S(0) must equal some other natural number, which we can denote by 1. Hence, we can define 1 as S(0) = 1.

Based on axioms 5, 6 \text{ and } 7 we are guaranteed the existence of at least two natural numbers, 0 \text{ and } 1, but not necessarily others.

For example, we could define \mathbb{N}_0 = \{0, 1\}, where S(0) = 1 \text{ and } S(1) = 1. In this case, both natural numbers 0 \text{ and } 1 have the same successor, which is 1.

If S(0) = 1 \text{ and } S(1) = 1, then the two natural numbers 0 \text{ and } 1 have the same successor, 1. This set of natural numbers together with the successor function S defined on it would still satisfy all the above axioms. However, if we stop here, the axioms constructed thus far do not guarantee the existence of the rest of the natural numbers that we know of, namely, 2, 3, 4 \ldots.

Therefore, our next axiom should ensure that different natural numbers have different successors. This means that every natural number is the successor of at most one natural number (since 0 is not the successor of any natural number) which implies that S must be an injective function.

Eighthly, no two natural numbers have the same successor unless they are equal.

Axiom \mathbf{8}. For all x, y \in \mathbb{N}_0, if S(x) = S(y), then x = y.

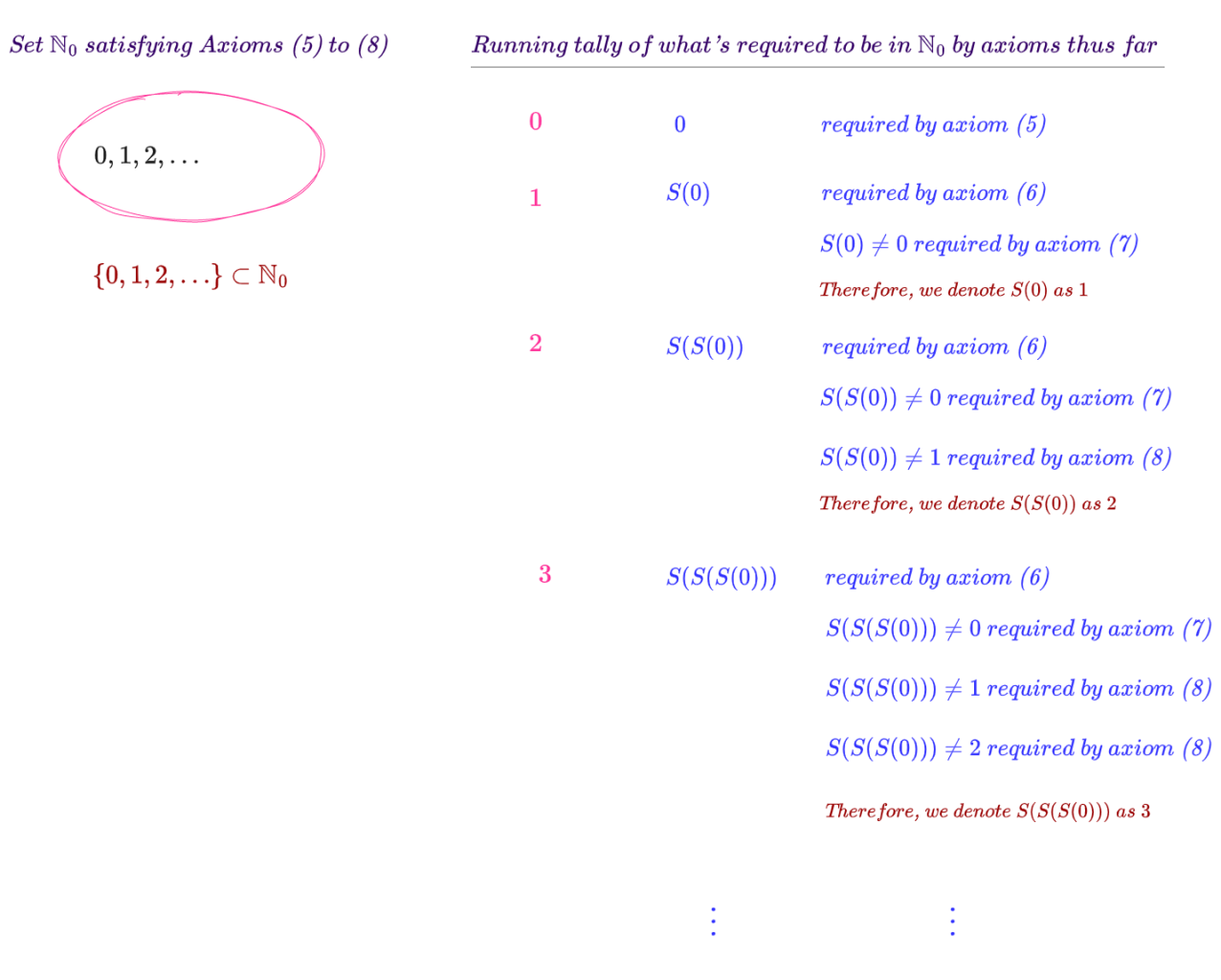

This axiom leads to some important consequences. It excludes the possibility of defining \mathbb{N}_0 to be just \{0, 1\}. We already have S(0) = 1 and since S is an injective function, we cannot have S(1) = 1. Axiom 7 excludes the possibility that S(1) = 0. Thus S(1) must be some other natural number, which we denote as 2. Therefore, we can define 2 = S(1).

By a similar argument, S(2) cannot be 0, 1 \text{ or } 2. Hence, it must be some other natural number, which we denote as 3. Continuing this way, we see that \mathbb{N}_0 must contain all the natural numbers that we know of.

So far we have established that \mathbb{N}_0 must include 0, its successor 1 = S(0), its successor’s successor 2 = S(1) and so on. Thus \mathbb{N}_0 must include 0, S(0), S(S(0)), S(S(S(0))), \ldots. In order to avoid so many nested applications of S we use the numerals 1, 2, 3 to denote S(0), S(S(0)) \text{ and } S(S(S(0))), respectively.

These first eight axioms have resulted in the definition of \mathbb{N}_0 to include all the natural numbers that we know of.

Therefore, so far we only know that

\{0, 1, 2, \ldots\} \subset \mathbb{N}_0

At this point, it is interesting to ask whether our axiomatic definition of \mathbb{N}_0 precludes the inclusion of additional elements.

In order to answer this question, let us consider a version of \mathbb{N}_0 that satisfies all the above axioms but is not the usual set of natural numbers that we know of. That is,

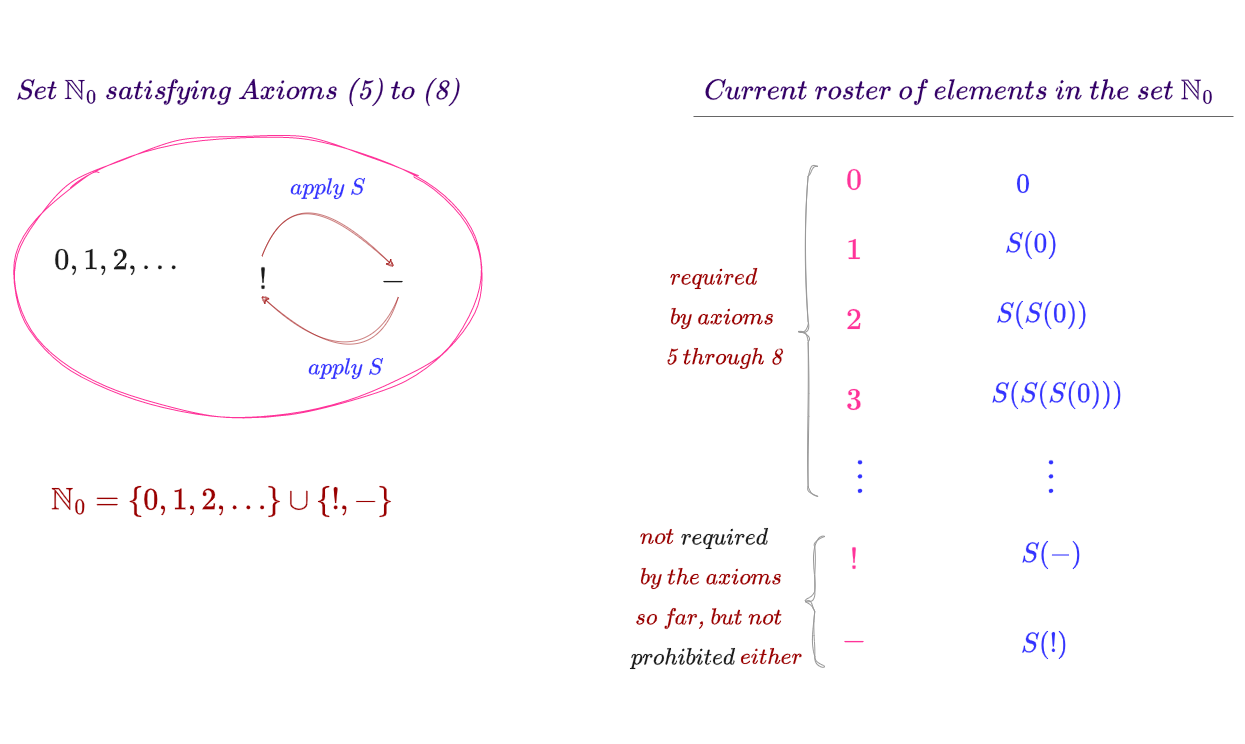

\mathbb{N}_0 = \{0, 1, 2, 3, \ldots\} \cup \{!, -\}As can be seen, this version of \mathbb{N}_0 contains all the natural numbers and also includes two other symbols, ! \text{ and } -.

We will next define the successor function on this set. For the subset \{0, 1, 2, 3, \ldots\} of \mathbb{N}_0, we define S as we have described above i.e., S(0) = 1, S(1) = 2, S(2) = 3 and so on. For the subset \{!, -\} of \mathbb{N}_0, we define S(!) = - \text{ and } S(-) = !.

This version of \mathbb{N}_0 with this successor function satisfies all the axioms, but it has more elements than what we want our set of natural numbers to have. This is shown below.

Similarly, there could be other versions of \mathbb{N}_0 with different successor functions, each of which satisfies all of the above axioms from 5 \text{ through } 8 but could also have elements other than natural numbers. This is illustrated below.

Based on axioms 5 \text{ to } 8, the set \mathbb{N}_0 of natural numbers satisfies the following conditions:

- 0 \in \mathbb{N}_0; and

- if x \in \mathbb{N}_0,\text{then } S(x) \in \mathbb{N}_0, where S(x) denotes the successor of x.

This way of defining a set, where a base clause specifies the basic element of the set and an inductive clause details how to generate additional elements, is called an inductive definition of the set, and such a set is referred to as an inductive set.

Therefore, the axioms 5 \text{ to } 8 only ensure that \{0, 1, 2, \ldots\} \subset \mathbb{N}_0, where \mathbb{N}_0 is any set such that 0 \in \mathbb{N}_0 and if x \in \mathbb{N}_0,\text{then } S(x) \in \mathbb{N}_0.

However, as discussed earlier and shown in the diagram above, this definition of \mathbb{N}_0 does not exclude elements other than natural numbers from being contained in the set. But we want only the natural numbers to be included in the set \mathbb{N}_0. To ensure this, the set \mathbb{N}_0 should be the minimal set that satisfies axioms 5 \text{ through } 8. This means that \mathbb{N}_0 is the intersection of all sets that satisfy these axioms. In other words, \mathbb{N}_0 contains only those elements common to all such sets.

Since axioms 5 \text{ to } 8 only ensure that \{0, 1, 2, \ldots\} \subset \mathbb{N}_0, in order to arrive at the set of natural numbers that we know of, axiom 9 should declare that \{0, 1, 2, \ldots\} = \mathbb{N}_0. But such a declaration would fail to capture the properties of the set \{0, 1, 2, \ldots\} as characterized by the axioms 5 \text{ to } 8. Therefore, axiom 9 \text{'s} description of this set should encompass its properties. The set \{0, 1, 2, \ldots\} \subset \mathbb{N}_0 can be unambiguously described as the subset of the set of natural numbers \mathbb{N}_0 that contains 0 and is closed under the successor function (meaning that if a natural number is in the subset, its successor is also in the subset). Therefore, axiom 9 should declare that any subset of \mathbb{N}_0, say T, that contains 0 and is closed under the successor function must equal the entire set of natural numbers, i.e., T = \mathbb{N}_0. The set \{0, 1, 2, \ldots\} always satisfies the conditions imposed on the set T and therefore, satisfies the premise of the axiom; but only when \mathbb{N}_0 = \{0, 1, 2, \ldots\} is the conclusion of the axiom, namely, T = \mathbb{N}_0, satisfied. Thus, axiom 9 effectively enforces the minimality of \mathbb{N}_0 and excludes any extraneous elements.

Let us peruse some examples to further illuminate the subtly of how axiom 9 achieves minimality.

Suppose we have \mathbb{N}_0 = \{0, 1, 2, 3, \ldots\} \cup \{!, -\} with the successor function as defined earlier. Then both T = \{0, 1, 2, 3, \ldots\} \cup \{!, -\} \text{ and } T = \{0, 1, 2, \ldots\} are subsets of \mathbb{N}_0. Both the sets contain 0 and are closed under the successor function. Therefore, both the sets satisfy the premise of axiom 9 but T = \{0, 1, 2, \ldots\} does not satisfy the conclusion of the axiom since T \neq \mathbb{N}_0. Therefore, \mathbb{N}_0 = \{0, 1, 2, 3, \ldots\} \cup \{!, -\} is not possible.

Through this example we have shown that if a larger set with extra elements other than the standard natural numbers were to be considered as \mathbb{N}_0, then the subset T of standard naturals within \mathbb{N}_0 would satisfy the induction premise i.e., the premise of axiom 9 and T would be forced to be equal to this supposedly larger \mathbb{N}_0, which is a contradiction.

Now suppose \mathbb{N}_0 = \{0, 1, 2, 3, \ldots\}. Then T = \{0, 1, 2, \ldots\} is the only set that satisfies the premise of axiom 9 and also its conclusion.

In essence, the axiom 9 defines the extent of the natural numbers. It says that the natural numbers are precisely those elements that can be reached by starting at 0 and repeatedly applying the successor function. Any set satisfying all five axioms cannot contain elements outside of this standard sequence.

This is illustrated below.

Axiom 9 uses the inductive definition of a set in its construction and is therefore referred to as the Axiom of Induction.

We will now state our ninth and final axiom. 😇

Axiom \mathbf{9} (Axiom of Induction). For any set T \subset \mathbb{N}_0, if:

- 0 \in T; and if

- x \in T \implies S(x) \in T for all x \in \mathbb{N}_0,

then T = \mathbb{N}_0.

As we have already discussed, the axioms 5 \text{ through } 8 ensure that \{0, 1, 2, \dots\} \subset \mathbb{N}_0.

We can see that T = \{0, 1, 2, \dots\} satisfies the premise of Axiom 9 since 0 \in T \text{ and } x \in T \implies S(x) \in T \text{ for all } x \in \mathbb{N}_0. Therefore, by the conclusion of Axiom 9, T = \mathbb{N}_0, which is only possible when \mathbb{N}_0 = \{0, 1, 2, \dots\}.

Thus we finally have the set of natural numbers that we know of, namely, \mathbb{N}_0 = \{0, 1, 2, \dots\}.

A Crucial Note on the Order of Logic

The Axiom of Induction as formulated above is a second-order axiom because it makes a statement about any subset T \text{ of } \mathbb{N}_0. This quantification over all possible subsets is a hallmark of second-order logic and is key to the power of this axiom in uniquely characterizing the set of natural numbers by excluding any extraneous elements, as our illustration above has shown.

In contrast, first-order Peano Arithmetic, operates within first-order logic, where we are restricted to quantifying only over the natural numbers themselves and not over sets of natural numbers. This restriction is a consequence of the fundamental design of first-order logic, which allows quantification solely over individual elements of the domain, explicitly excluding quantification over sets of elements and thereby giving rise to desirable meta-logical properties like completeness, meaning that if a statement is logically valid, it can be proven within the system. Second-order logic, while being more expressive (like the ability to fully characterize \mathbb{N}_0), typically lacks this property of completeness. We will delve into these meta-logical properties in more detail later.

To capture the idea of induction within this first-order framework, we use an axiom schema. This schema provides a separate axiom for each formula \phi(x) in the language of first-order arithmetic. Essentially, for every property of a natural number x that can be expressed by a first-order formula \phi(x), we have an axiom of the form:

(\phi(0) \land \forall x \in \mathbb{N}_0(\phi(x) \implies \phi(S(x)))) \implies \forall n \in \mathbb{N}_0 \, \phi(n)Therefore, this schema provides an infinite number of axioms, one for each such property. While aiming for the same inductive power, the inductive principle in first-order Peano Arithmetic is limited to properties formally expressible within its language, which is insufficient to fully express all the properties of standard natural numbers due to the constraints of first-order logic. Consequently, axioms of first-order Peano Arithmetic do not guarantee that \mathbb{N}_0 is limited to the standard natural numbers \{0, 1, 2, \ldots\}, allowing for the possibility of additional elements that also satisfy all the axioms. The second-order formulation, by ranging over all possible subsets, avoids this limitation.

We will delve into the specifics of the language of first-order arithmetic and the implications of this axiom schema later in our discussion. For now, it’s important to note this key difference in how induction is formalized in first-order logic compared to the second-order formulation we are currently examining.

Alternate Formulations of Axiom of Induction: Set-Based and Predicate-Based Perspectives

For the sake of completeness, we will discuss two alternate yet equivalent ways to formulate Peano’s Ninth Axiom, namely the Axiom of Induction. Their equivalence stems from the fundamental and often intertwined relationship between sets and their characteristic predicates, a connection that underpins much of mathematical logic.

As a cornerstone of number theory, the Axiom of Induction, which we have already seen in its set-based form as Axiom 9 (where the conclusion implies a set T, initially a subset of \mathbb{N}_0, must indeed be equal to \mathbb{N}_0), can also be expressed through the lens of properties or predicates. The set-based formulation can also be presented with the conclusion that \mathbb{N}_0 \subset T, which, given the premise that T \subset \mathbb{N}_0, leads to the same result as T = \mathbb{N}_0. This leads to two primary, though ultimately equivalent, formulations: the set-based formulation and the predicate-based formulation. Each offers a distinct yet complementary perspective on the same underlying logical structure.

Set-Based Axiom of Induction: Focusing on Subsets

Axiom \mathbf{9} (Axiom of Induction). For any set T \subset \mathbb{N}_0, if:

- 0 \in T; and if

- x \in T \implies S(x) \in T for all x \in \mathbb{N}_0,

then \mathbb{N}_0 \subset T.

In simpler terms, if any subset of natural numbers contains 0 and is closed under the successor function (meaning that if a natural number is in the subset, its successor is also in the subset), then that subset must contain all natural numbers.

As discussed above, Axioms 5 \text{ through } 8 ensure that \{0, 1, 2, \ldots\} \subset \mathbb{N}_0. Additionally, we observe that the set \{0, 1, 2, \ldots\} satisfies the following two conditions of Axiom 9:

- It contains 0; and

- Whenever it contains an element x, it also contains its successor, namely, S(x).

Therefore, by Axiom 9, it follows that \mathbb{N}_0 \subset \{0, 1, 2, \ldots\}.

Since Axioms 5 \text{ through } 8 ensure that \{0, 1, 2, \ldots\} \subset \mathbb{N}_0 and by Axiom 9 we have show that \mathbb{N}_0 \subset \{0, 1, 2, \ldots\}, it follows that \mathbb{N}_0 = \{0, 1, 2, \ldots\}.

This perspective emphasizes the structure of the subset itself. We are concerned with the elements that are members of the subset and how they relate to each other through the successor function.

Predicate-Based Axiom of Induction: Focusing on Properties

Peano’s axioms five through eight collectively define a superset of natural numbers, specifically \{0, 1, 2, \ldots\} \subset \mathbb{N}_0. To ensure that this set \mathbb{N}_0 includes only natural numbers, Peano’s ninth axiom can also be formulated as the principle of mathematical induction over natural numbers. This formulation is equivalent to the axiom of induction and serves the same purpose of removing unwanted elements from the superset \mathbb{N}_0, ensuring that it contains only natural numbers.

The predicate-based form of the Axiom of Induction shifts the focus from subsets to properties (expressed as predicates) that natural numbers may or may not possess.

The reformulation of Axiom 9 in terms of predicates results in the Principle of Mathematical Induction which is stated as follows.

Axiom \mathbf{9} (Principle of Mathematical Induction). For any predicate P(n), where n is a natural number, if:

- P(0) is true, and

- for every natural number n, P(n) being true implies that P(S(n)) is also true,

then P(n) is true for every natural number n.

Here, we are concerned with a property (represented by the predicate P(n)) that natural numbers might possess. If 0 has the property, and if natural number n having the property implies that its successor S(n) also has that property, then all natural numbers must have that property.

This perspective emphasizes the properties of individual natural numbers. We are concerned with whether a given natural number has a specific property.

Equivalence and Connection

The set-based and predicate-based forms are logically equivalent, meaning they express the same fundamental principle. This equivalence is rooted in the relationship between subsets and predicates, as established by the Axiom of Separation.

- From Subset to Predicate:

- Given T \subset \mathbb{N}_0, it implies from the Axiom of Separation that there exists a predicate P(n) such that P(n) is true if and only if n \in T.

- Given T \subset \mathbb{N}_0, it implies from the Axiom of Separation that there exists a predicate P(n) such that P(n) is true if and only if n \in T.

- From Predicate to Subset:

- Given a predicate P(n) and a set \mathbb{N}_0, we can define a subset T = \{n \in \mathbb{N}_0 \,|\, P(n) \text{ is true}\}, by the Axiom of Separation.

Using this correspondence, we can see how the two types of formulations of axiom 9 map onto each other:

- \text{``}T \subset \mathbb{N}_0 \text{"} (Set Formulation – Considering a subset of natural numbers) is equivalent to \text{``}P(n), where n \in \mathbb{N}_0 \text{"} (Predicate Formulation – Considering a property of natural numbers).

- \text{``}0 \in T \text{"} is equivalent to \text{``}P(0) \text{ is true"}.

- \text{``}x \in T \implies S(x) \in T for all x \in \mathbb{N}_0 \text{"} is equivalent to \text{``}P(n) being true implies that P(S(n)) is also true for every natural number n\text{"}.

- \text{``}\mathbb{N}_0 \subset T \text{"} is equivalent to \text{``}P(n) is true for every natural number n \text{"}.

It should be noted that if \mathbb{N}_0 \subset T, then the Axiom of Separation guarantees the existence of a predicate P(n), where n \in T, such that P(n) is true if and only if n \in \mathbb{N}_0. Since n \in T \text{ and } T \subset \mathbb{N}_0, n is a natural number, i.e., n \in \mathbb{N}_0 is always true. Therefore, the statement becomes \text{``}P(n) is true for every natural number n \text{"}.

Thus, the subset and predicate perspectives are simply two ways of expressing the same fundamental idea. The set-based form emphasizes the elements within a collection, while the predicate-based form emphasizes the properties of individual elements. The Axiom of Separation is the bridge that allows us to move seamlessly between these perspectives.

Why Both Forms Are Useful

Both forms of the Axiom of Induction are valuable tools in mathematical proofs. The set-based form is often used in set theory and related areas, where the focus is on the set of natural numbers constructed based on some property, while the predicate-based form is commonly used in number theory and other branches of mathematics, where properties of numbers are the main focus. Essentially, they are two sides of the same coin, and which one to use depends on the context of the problem and the preference of the mathematician.

The predicate-based form of the Axiom of Induction has historical precedence over the set-based form. Principles resembling mathematical induction can be traced back to ancient Greek mathematicians like Euclid, who used methods akin to induction in some of his proofs, although not in a fully formalized way. Later, mathematicians like Blaise Pascal in the 17th century and Pierre de Fermat employed inductive-like arguments more explicitly. However, the first clear and rigorous formulation of the Principle of Mathematical Induction as we know it today is often attributed to Augustus De Morgan in the mid-19th century. His work explicitly stated the base case and the inductive step in a manner very similar to the predicate-based form we use now. The set-based formulation arose later with the formalization of set theory in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, becoming particularly prominent in the context of how the natural numbers are understood based on the fundamental axioms defined by Giuseppe Peano. His axiomatic system provided a characterization of these numbers that could be realized as a specific set within set theory, thus leading to the set-based formulation of induction.

The Mathematical Structure Defined by the Peano Axioms

The Peano axioms define a specific mathematical structure (\mathbb{N}_0, S, 0), where \mathbb{N}_0 is the set of natural numbers, S is the successor function, and 0 is a distinguished element. The axioms themselves specify the fundamental relations and properties that give this structure its unique characteristics.

Method of Definition of Natural Numbers using Peano’s Axioms

It should be noted that Peano’s Axioms only describe how to construct the set of natural numbers and do not define what natural numbers are intrinsically. The axioms essentially provide an inductive definition of the set \mathbb{N}_0: 0 is the initial natural number, and for every natural number n, its successor S(n) is also a natural number. Every natural number is identified by its unique generation through the repeated application of the successor function starting from 0. For example, the natural number 2 is represented by S(S(0)) and is obtained by starting from 0 and then applying the successor function once and then again to 0. The fact that nothing else is a natural number beyond what can be generated in this way is ensured by the Axiom of Induction, which guarantees the minimality of the set \mathbb{N}_0 satisfying these properties.

Existence of the Set of Natural Numbers satisfying Peano’s Axioms

How do we establish the existence of a set, an element of that set, and a function from the set to itself, that satisfy Peano’s Axioms? These axioms themselves are insufficient to prove this existence. Consequently, there are two approaches to resolving this matter.

One common approach in mathematics is to take something as axiomatic and then use it as the basis upon which we prove all our other results. Hence, such an approach requires us to be satisfied with taking the existence of a set satisfying Peano’s Axioms axiomatically. This axiom is called the existence axiom for natural numbers and guarantees that there exists a set with the properties that Peano’s axioms ascribe to it.

The statement of this axiom is as follows:

Existence Axiom for Natural Numbers: There exists a set \mathbb{N}_0 satisfying Axioms 1 \text{ through } 9.

Alternatively, if we use the Zermelo-Fraenkel Axioms as our foundation for set theory, we can prove that something satisfying Peano’s Axioms exists, so we don’t need to assume it separately. We’ll show how this is done later. This approach is often preferred as it seeks to build mathematics from a more minimal set of fundamental axioms. Nevertheless, studying Peano’s Axioms as an independent axiomatic system, including assuming the existence of a set satisfying Peano’s Axioms, allows us to explore the properties of this axiomatic system and its consequences in isolation from a specific foundational embedding.

Proving Properties of Natural Numbers

Having established the existence of the natural numbers and their fundamental properties as defined by Peano’s Axioms, we will next explore how to rigorously prove that the natural numbers satisfy a given property using the Axiom of Induction.

Next Topic: Proving Properties of Natural Numbers Using Proof by Induction